Your basket is currently empty!

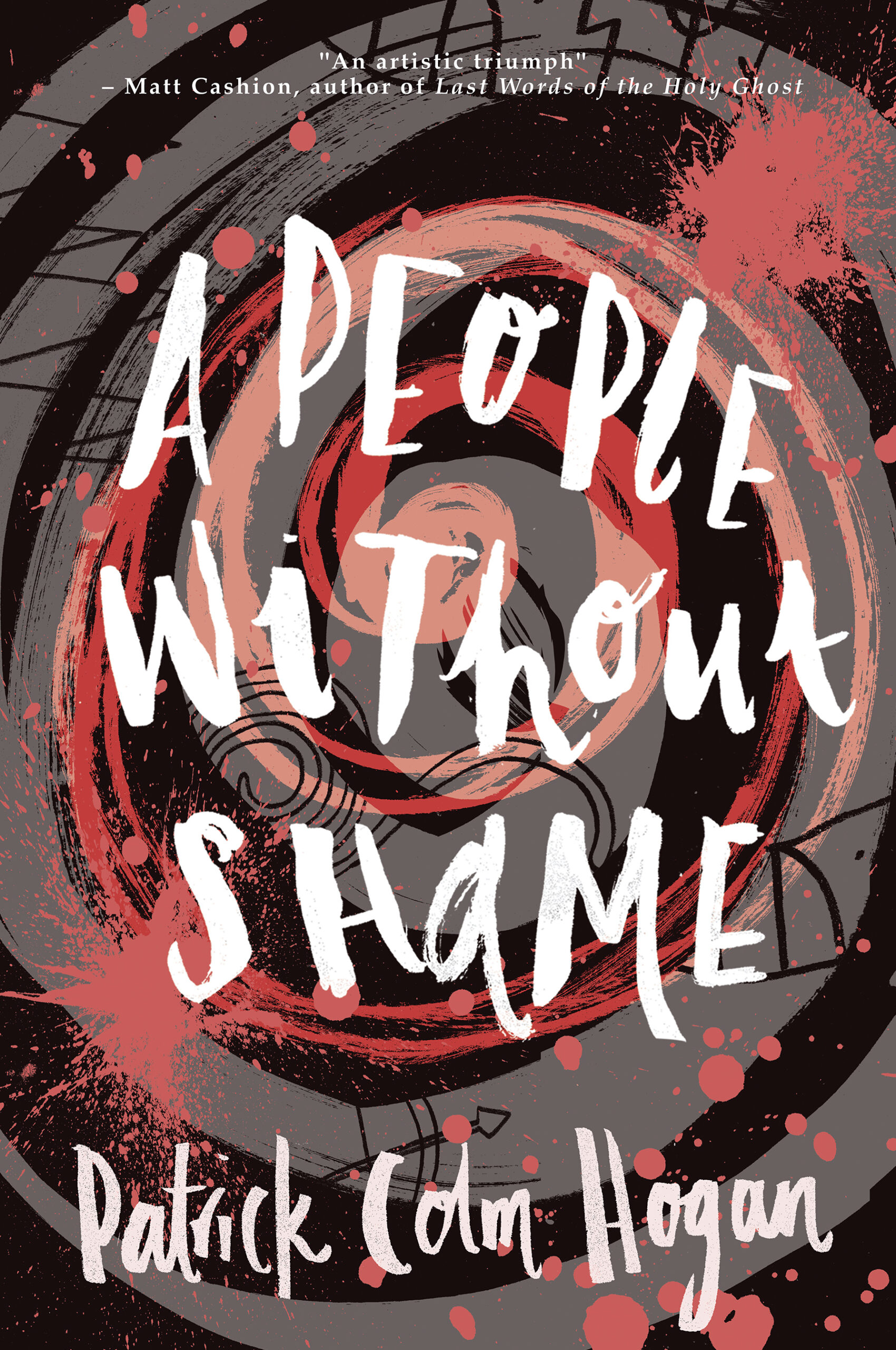

A Q&A with Patrick Colm Hogan

JR: A People Without Shame is a strange book, full of contrasting parts. At times diary, at times legend, at times transcript, at times article, it seems as though the novel is trying to demonstrate how difficult it is to convey its subject matter in a conventional manner. What do you think of this interpretation?

PCH: Yes, that seems to me right. I didn’t think of it in precisely those terms, but I agree. Perhaps surprisingly, I thought of it more from the reader’s side than from the author’s. Specifically, we are always given only diverse and fragmentary sources, with necessarily partial and to some degree biased construals of events. Then we have to figure out what happened, relying on somewhat opaque and surprisingly malleable testimonies of limited reliability. Actually, this is the case even from the author’s perspective, and even if the work is itself testimonial. Specifically, empirical research has shown that our memories of events alter with the circumstances in which they are recalled. In that sense, even someone who experienced the actual events has to puzzle out—as if from blurry photographs and recordings distorted by static––what really happened.

JR: Yes, with several of the events mentioned in the book there is no way to truly know what happened, due to the opacity, and due to bias and misinformation. It’s nice that we don’t see that anymore these days, isn’t it?

PCH: Despite the ellipses, problematic chains of transmission, etc., I actually think we end up with a pretty solid idea of most major events in the novel (though, as you say, there are some that remain bewildering). For example, our initial information about Songari prisons is basically hearsay. But when A. ends up in a Songari cell, there are enough confirmatory details to indicate that the “hearsay” is well-founded. Also, A. is not omniscient and he does have biases (like everybody). But, in my view, he merits our trust in both his general competence and good intentions. Sometimes a postmodern writer will suggest that we cannot ever really get at the truth (or, what is more extreme, that maybe there is no such thing as the truth). I wanted to indicate that, despite difficulties, this is not the case. Most often, we can get a good idea of the truth—though, in evaluating the evidence, alternative explanations, and so on, we need to be aware of the very serious problems we face (again, even with our own personal experiences).

JR: You have dedicated much of your life to studying colonialism, and until now have chiefly written scholarly non-fiction on the subject (as well as many others). After authoring over twenty academic books, what motivated you to take the plunge into fiction?

PCH: Actually, things happened in the opposite direction. I was writing poetry from 7th grade on. In 1972, as a freshman in high school, I won a poetry contest in Kansas City, announced at an event which featured a reading by Mona van Duyn (later to become a poet laureate of the United States) and earning myself the royal sum of $25 (apparently equivalent to $181.44 today). It is worth noting that it was an anti-war poem (A People Without Shame is, perhaps before all else, an anti-war novel). Twenty-five years later, perhaps unconsciously emboldened by this early approbation, I wrote a book-length, narrative poem, based on Hindu goddess myths. I had no success in publishing it until 2014. While trying to publish that, I wrote and repeatedly revised A People Without Shame. I had much more success with scholarly writing, which led me to devote my time and effort to that. Even so, the two types of writing have remained inter-connected for me. For example, later this year, Routledge will publish my most recent scholarly book, What is Colonialism?, which derives in part from my work finishing up A People Without Shame for Blackwater. Indeed, the critical book in some ways (indirectly) explains what I am doing in the novel.

JR: And what did you spend your $25 on?

PCH: Probably LPs—The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Grateful Dead; the sorts of things other kids my age were buying. If I bought poetry, it would have been e. e. cummings.

JR: From where in particular did you draw your influences when you were creating Somota, and when penning the epic of Garuna that is woven through the book? When A. arrives and introduces us to it, it feels like a very real place.

PCH: Thanks. The sense of reality (insofar as people do indeed feel that) probably has two sources. First, the main characters and the things they do have sources in my own, biographical experiences. Though I re-imagine them in a very different context (something that our minds have evolved to do pretty well), I feel that the original motives, beliefs, rationalizations, and so forth, remain plausible in the new circumstances. Second, I have tried to push myself to give considerable detail, thereby making the places, events, and people more distinct and particular in the reader’s imagination (or “simulation,” as cognitive scientists would say). This tends to foster a sense of reality in part by fostering an emotional response.

As to influences, those are of two types—historical and literary––which also (I hope) contribute to the sense of reality. As to the former, I have sought to base most of the particular occurrences in the novel on historical precedents. Examples range from the missing generation of Somotan men (derived from the radical reduction in men of the draftee generation in the U.S.S.R., due to German colonialism), to the preoccupation with hunger (due to a range of colonial policies that have consistently rendered colonized societies food insecure), to the nature of the conquest of Somota (which is modelled on the conquest of Igboland), to some aspects of the insurgency (which are based on actions of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army). More complex structures also have historical sources. For example, the broad organization of the region by reference to the northern Songari, the south-western Kelans, and the south-eastern Somotans is modelled on Nigeria, with the Hausa-Fulani to the north, the Yoruba to the south-west, and the Igbo to the south-east.

As to the literary sources, people will probably remark most readily on the use of the Mahabharata in The Dream of Garuna, with the five ruling brothers, the disenfranchised eldest brother, and so on. But I draw almost as much on Exodus, with the abandonment of Garuna in the river to his leading his people out of the land of their bondage. I draw also on a range of myths ranging from the puranas of India to the oral tales of the Americas, sometimes as recounted in Levi-Strauss’s magisterial multi-volume Mythologiques. I was surprised to be reminded of the relevance of the story of Sin and Death, when I had to re-read Paradise Lost recently. When I listened to an audiobook of Vergil, I was also surprised to see the recurring influence of the Aeneid on the treatment of war in the novel. There are no doubt many other, forgotten influences of this sort. Modern works have of course had an impact as well. I have often emphasized Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians. Joyce’s Ulysses is a more subtle, but pervasive presence.

JR: In saying you pushed yourself to give considerable detail so as to foster a sense of reality in the reader’s imagination by fostering an emotional response, you make storytelling sound quite formulaic. Is it?

PCH: Well, it is in part formulaic. I’ve argued (in, for example, What Literature Teaches Us About Emotion) that emotional elicitors are not a matter of broad evaluation, but of concrete perception or imagination. That has partially formulaic consequences, but only partially. Here’s a simple example. Someone might write a story about a first date, including the statement, “We went to a restaurant and had something to eat.” For a particular story, this might be the most appropriate thing to write. But it would probably be better to develop some details in the vast majority of cases. Contrast the preceding, generic statement with deciding to forego the restaurant when the two of you see a popsicle stand, then—on reading the available flavors––puzzle over just what is a boysenberry is, or the two of you go to the restaurant, but end up only sharing a dessert, due to the scandalous prices. There isn’t a single right way of doing this for every story, and sometimes writers will make disruptive blunders in trying to be particular, thereby breaking the emotional continuity of the piece and undermining the effect. But, for the most part, such particularity is, I believe, more likely to foster engagement, emotional response, and a sense of reality.

JR: Kehinta is a compelling character. How would you describe her to those who haven’t read the book?

PCH: She is the Somotan bard in charge of preserving the main oral epic and of refashioning it to serve the social and political needs of her society. But, like other Somotans, she also does manual labor—fishing, when she is in a traditional, Somotan community. Unlike our stereotype of a poet, or our gender stereotypes, she is not at all romantic. She works with A, not for the wonders of poetry—still less from some exaggerated respect for Europeans in general or A. in particular––but for the medical supplies he arranges in payment. She has a pragmatic, non-moral response to sexuality (though, of course, she despises force or coercion in sexual relations). On the other hand, she is almost certainly more vulnerable than she appears. That discrepancy is mainly due to the fact that she hardly ever shows weakness. Like a traditional Igbo man (such as Okonkwo in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart), she will fairly readily express anger, but only hints at sorrow or fear. Those moments come, for example, when she alludes to her husband’s death, or when she becomes concerned, however briefly, that A. has set her up to be an informant. This isn’t a cultural trait, by the way, but an individual trait. For example, the other woman who is assaulted in the novel reacts with great fear and sorrow.

JR: For how long had the novel been in the works? Did any particular parts come first?

PCH: About 25 years. At this distance, I can’t recall what I wrote first and what came after. I do remember that I did a lot of “scholarly” background work to guide the writing. For example, I outlined out some principles of the Somotan and Kelan languages (both imagined as Indo-European languages) in contrast with Songari (a Semitic language). I also sketched a more detailed geography. I don’t know where any of those notes might be now; I probably discarded them.

JR: We must discuss your protagonist A., and the difficult themes the book addresses. A. often laments that he is in a painful position. He is keenly aware of his status as part of the colonial regime, disparaging of the Reverend G. and the government’s mission, and frequently faces discrimination himself. Yet, he is simultaneously too afraid to do much of anything about the injustices surrounding him. And of course, when compared to the people of Somota, who face the destruction of their culture and the massacre of their communities before his eyes, the reader is keenly aware that he is really not in such a painful position at all. What do you think of A.? Do you like him? He doesn’t seem to like himself very much.

PCH: Somotan traditions (in the novel) suggest that the more ethically sensitive one is, thus the more moral one is, the more keenly one is conscious of one’s sinfulness. I think A. is a very humane character and he does act with genuine moral courage. But he is deeply aware of just how little he has tried to do, the times when he has not tried to do anything at all (as in the case of the Kelan weavers), and how ineffective he has been even when he has tried to do something. His first problem is that he is naïve. But he is open to learning and does learn, if incompletely. Moreover, he does face real dangers. First, there is the possibility of continuing imprisonment, with all that suggests about his future. Then there are the implied dangers to Kehinta, suggested by G. It is also critically important that there is no clear social context in which he can join with others in shared anti-colonial work. Such a context is necessary if anyone is going to accomplish anything positive, whether against colonialism or any other social harm.

JR: And a comment on the discrimination A. himself faces. He is Jewish, and Irish, among predominantly English fellows – correct? What motivated this character background?

PCH: Well, the Irish part is me. (I did one of those genetic tests a couple of years ago and it claimed that something like 90% of my genetic ancestors came from Clare or Cork; evidently, we didn’t travel much.) This allowed me to talk about the anti-colonialism in my extended family, basically just attributing it to A.’s background. The Jewish half is due in part to my mother’s repeated claim that, if she weren’t Catholic, she’d be Jewish. I briefly misunderstood this as a child, but soon came to realize that it was just her hyperbolic way of saying that she would never be a Protestant. Much more importantly, I wanted A. to have some more direct experience of personal discrimination. His Irish background gives him a connection with social poverty and the like, but he does not experience much personal discrimination, except perhaps from other Irish characters.

JR: Have you or will you ever write anything else based in Somota?

PCH: I had never thought about it, but on reading your question, I immediately thought that it would be possible to write a work about, say, two linguists, one Somotan, one European, who are working on the language in independent Kela; the European, upon reading A People Without Shame, begins to suspect that his colleague is Kehinta’s daughter. That would probably never be resolved. This story might be intercut with news reports or Kelan television ads, or something else rather different from the translations in A People Without Shame. I think it might work. But my health probably won’t allow me to undertake such a project.

JR: What books have you read that influenced how A People Without Shame has turned out?

PCH: I’ve already mentioned a number of them. I might add works on colonialism, especially in Southeast Asia and Central and South America. Indeed, though the colonialists in the novel are British, the concerns that drove the writing of the novel were far more about U.S. imperialism in, for example, Guatemala or Chile. (This reminds me that the novel is also influenced by cinema, such as Costa-Gavras’s Missing and Z.)

I should also add works on ethics, both various of Kant’s writings and work on dharma theory in Hindu tradition. A recurring theme in Somotan culture in the novel—a theme that I’m afraid might readily lend itself to misinterpretation—is that the moral quality of an act is not reflected in the benefits of its outcome for the agent. Somotan ethics is, so to speak, the diametric opposite of prosperity theology. For example, what happens to Kahngee in no way suggests that what she did was wrong.

JR: A word on the epic of Garuna, and the various other myths and folktales scattered throughout the book. How did you find the shift between writing in this style, and writing from the point of view of A.?

PCH: I have written fairly many imitations of different styles over the years. It wasn’t to train myself, but just for fun. A few were part of academic articles. They were sometimes imitations of chapter styles in Ulysses. They were sometimes other things—for example, Nabokov’s Pale Fire or the speech of some public figure, such as Joe Biden. As a result of this (inadvertent) practice, I found it easier to switch styles than it might have been otherwise.

JR: Finally, looking back on the book now, is there anything in there that surprises you, that you did not expect to feature in a book published with your name on it?

PCH: There are certainly things that would have surprised younger me. But I drafted the book long enough ago that what is there does not surprise me now. I am a bit surprised that I seem to have left out most of the embarrassing errors that were present in earlier versions. That is due, in part, to your careful readings, as well as those of Elizabeth and Vivien.

JR: Agreed, we deserve all the credit…

PCH: Actually, the three of you do deserve the credit of seeing value in the book, so that it has been “published with [my] name on it.”

Leave a Reply