Your basket is currently empty!

Author: admin

Q & A with John Fulton

JR: How did your first forays into writing compare to the work you publish now?

JF: It depends on what you mean by my “first forays,” which were way back in my college/university days. I was experimenting then, playing around with language, seeing what I could do, what sort of voices and linguistic acrobatics I was capable of. When I first started putting regular time in at the desk, it was the early 1990s and I was heavily influenced by Raymond Carver, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Italo Calvino, and Angela Carter, among others. I was trying to write at once gritty realism and magical realism. That was a challenging combination to pull off, and it mostly didn’t succeed. It’s hard to write in the shadow of Marquez. Any attempt to sound/be like him will make the aspiring writer look small. But it was fun. Later, when I moved to continental Europe for four years, I was heavily under the spell of Gordon Lish, an influential editor who was big in the US. He was a proponent of an extreme kind of minimalism (a lot less is a whole lot more) and “dirty realism” or what some called “kitchen sink realism,” which means everyday life with some tough living thrown in: lots of alcohol, bad relationships, people living on the edge of poverty. He was the fiction editor of Esquire and then an important book editor at Vintage. He launched the careers of Raymond Carver, Barry Hannah, and Amy Hempel. My first published story was in a magazine Lish edited called The Quarterly.

Ultimately, that kind of writing, in which everything was implied and shown and almost nothing was said, left me feeling gagged and bound. Most of my stuff was no longer than 2-4 pages. I was living in Berlin, Germany, at that point, learning German and reading a lot in that language, including the original versions of The Brothers Grimms’ fairy tales, which are astonishingly good and nothing like the Disney versions I’d grown up with. That left me wanting to write even more in a fable-like mode, which often didn’t work for me.

It wasn’t until I moved back to the States to attend the University of Michigan MFA program that I broke free of that sort of writing. I discovered the stories of early Richard Ford, Alice Munro, Denis Johnson, and Joy Williams, and started writing longer form stories in the tradition of psychological realism. The writing I did in that program and for a few years after finishing at Michigan made it into my first collection. I was writing stories that cut immediately to conflict and veered towards crisis and more explosive material. For example, in one story, a janitor who works at the local YMCA gets drunk, puts too many chemicals in the pool, and thinks he’s blinded a little girl who jumps into the toxic water. He loses his job, goes home, drinks some more, fights with his wife, and struggles to rid himself of the terrible guilt he feels. There was humor in these stories, edgy writing, and often extreme events. I was also writing a lot about adolescent characters, whom I still find fascinating. Adolescents are natural rebels and sharp critics of the adult world even while childhood and innocence have become embarrassing—a source of shame for them. They’re stuck between worlds with nowhere to go. The title story in my first collection, “Retribution,” is about a 15-year-old girl whose mother is slowly dying. She’s angry, confused, has a deep infatuation with a German exchange student, and ends up intentionally hurting her driver’s education instructor. But there was a quietness in that story, a patience, that was new to me. This story was about fifty pages, the longest I’d ever written. In short, it suggested new directions, new possibilities for my work.

My current stories now are less conflict based, often less explosive and crises oriented, though there’s still a fair amount of tension in them. “Box of Watches” unfolds around an armed robbery in a pawnshop; “The Flounder” is about a couple struggling with an episode of infidelity that the wife confesses to her husband, the night before they leave their home in Switzerland for a vacation in France. But the stories take their time, they expand and explore character and situation over more pages than my earlier work. While I still like to write about adolescents, young characters take up fewer pages in The Flounder. I’m in my fifties now and am writing more about the relationship between generations, the young and the elderly. In fact, it wasn’t until I started reading the proofs for this book that I realized just how interested my more recent stories are in older characters who are aware of being close to the end of life, who remember and recall more than they look forward. My influences have changed, too. One of my favorite writers more recently is the great Irish novelist and short story writer, William Trevor. There’s a quiet tension in his work that is breathtaking, odd, and deeply unique to him. His stories develop with patience and move towards climaxes that can feel both muted and incredibly powerful.

In The Flounder, I’m also writing about a time in my life when I lived in Europe, mostly in Switzerland and Berlin, Germany, for four years. This was a challenging, if rewarding, experience. I was in my mid-twenties, in my first serious relationship, which was difficult and finally didn’t work out, and very aware of being American. For years, I tried to write about this time without much success. Then, in 2019-2020, I moved to France for a year with my family and the stories about this era in my life, which was a time of travel, mobility, and discovery, started to flow just as lockdown began in March of 2020. Something about being shut into a room and not being able to circulate freely gave rise to and access to that material. A lot of these stories were written or begun in lockdown. One thing I’ve learned about myself is that I often need many years, even a decade or more, to write about a formative experience.

JR: And if you had to recommend one Brothers Grimm tale?

JF: We all know these tales through Disney, which sanitized them. But the Grimms’ versions are brutal, violent, and graphic. I’d recommend dipping into one of the more familiar stories like “Cinderella.” We all think about this as a girl-meets-prince-charming story, which it is. But the reader hardly notices the happy ending here because it’s proceeded by such extreme abjection (a young girl’s beloved mother dies suddenly, after which her father quickly marries a sadistic, materialistic woman whose daughters torture and enslave Cinderella. This young girl not only works constantly but is fed sparingly from leftovers and kept like a farm animal. My favorite part is the revenge exacted on the stepsisters, who are so desperate to catch the prince that they carve large parts of their feet off (a big toe and a heel) to fit into the slipper. Their mother actually hands the knife to them and assures them that they won’t really need to walk once they’re the princess. The shoe fits, but soon enough the prince can see blood gushing from it and he’s not fooled.

By the way, a number of European fairy tales and folktales snuck their way into the stories in The Flounder (“Hansel and Gretel” in “Saved,” “The Fisherman and His Wife” in the title story, and “The Death and the Maiden” in “Budapest”). Perhaps this should come as no surprise since I was reading them during my years abroad and have been obsessed with them ever since. While I my stories are realistic, these tales, which contain surprising insight about human desire, sexuality, and greed, infuse the work in places with a bit of strange magic. At least, that’s my hope.

JR: You’ve discussed the gradual shift in style and subject matter. But are there any eurekamoments you can recall, moments that altered how you approach the task of writing? Or has it always been a gradual enterprise?

JF: I wish there were. I’ve heard many writers say—and I’ll concur with them—that every project feels as difficult and challenging as the first successful story or novel. The challenges of any given project are often unique and require new ways of thinking, new strategies, new solutions. That said, discovering material (what it is that one needs to write about) can liberate my work for a period of months or years until I’ve written through or reached the end of that material. I’ve also learned over the years that part of my process is arriving at impasses, places where the work just stops. When this happens, I usually need to do one of two things: work in a different direction or—and this is wretchedly hard for me to do—give up on the project. Forcing a story or novel is about the worst feeling I’ve encountered at the desk. There’s wisdom in knowing when to put something away. I do this a lot only to return, look at the pages with fresh eyes, and see something that I couldn’t see before and that allows me to finish the thing and often publish it.

Here’s one illustrative example: I began writing “Box of Watches,” which is included in The Flounder, more than 20 years ago. In 2017, I recalled that material—the pawnshop, the armed robbery, the grandfather—and felt the pull it still had on me. When I dug a very rough and incomplete draft of the story out of a box, I knew what to do with it and finished the story in a few days. There might be some “eureka” in that: know when to quit; know when to start again.

JR: For the most part the stories you tell in The Flounder are rooted in reality. Strange things happen – an imagined Charles Manson lurks in the shadows of “The Boy and the Murderer”; in “Box of Watches”, a gunman enters a pawnshop carrying a “box of used-up time.” But you seem to seek out the absurdities present in everyday life, rather than setting your fiction in worlds with different rules. What do you make of this interpretation? Are you ever tempted––and I had written this question even before you mentioned Marquez and Calvino!––are you ever tempted to take a step further in that direction, towards the speculative or the surreal? Or is the real world strange enough?

JF: I think you’re right: I work from the familiar towards the strange. And yes, as I say above, I’ve deeply admired authors like Marquez and Calvino, who work in the opposite direction: they need to ground their magical and/or absurd visions in the familiar or everyday world so that the reader sees its relevance and relatedness to lived experience. An old man with wings falls out of the sky (Marquez) or a man spends his entire life living in trees (Calvino). That’s wonderful, a kind of circus mirror that shows us what we often forget: how strange humanity really is. I think a lot of art does that. It delivers or returns us to a vision of awe and wonder at human experience—something we forget because we’re beaten down by routine, money making, survival, and the fatigue of being sensory creatures. We’d be overwhelmed if we really saw the variety and complexity of the world in front of us. There’s no time to really look at that bench at the bus stop or the tree next to it because you’ve got to get on the bus and get to the office.

But if you’re working in the realm of the familiar (otherwise known as “realism”), you need to find ways to show the reader why that bench and tree deserve and reward a closer look and might even remind us of the awe and strangeness that we’ve forgotten and that is everywhere around us. My mentor in graduate school, Charles Baxter, writes a wonderful essay about this called “On Defamiliarization.” Baxter talks about various strategies that writers employ to compel the reader to pay closer attention, to observe and see more carefully.

In many of the stories in The Flounder, there’s a kind of trap door that opens into a slightly strange or dreamlike vision, usually somewhere towards the middle. This transition is enabled by syntax, tone, and diction. One example: In the title story, Marian confesses to her husband Daniel that she’s just slept with someone else the night before they go on a short vacation. This isn’t exactly a new story: writers have been interested in infidelity for centuries. There is both tension and stakes in it. There’s also the challenge of showing the reader something unexpected about this particular couple and their struggle with a familiar problem. When they leave their home in Switzerland (what nation is more grounded in the stuff of everyday life—money, jobs, security, and routine—than this one?) and cross the border into France (a clear counterpoint to Switzerland), things change. A huge storm engulfs them. They arrive wet, frightened, and in the dark at their hotel, where they’re the only guests. Of course, the reader will recognize these elements. We’re in the realm of the gothic, the slightly scary, the fever dream. The hotel keepers are a long and happily married couple, and when the woman greets our troubled young Americans at the reception desk, her clothing is askew and there’s something at once pragmatic and sensual about her. She promises the couple a dinner in the hotel dining room with a delicious and magical fish as the main course. The meal they share is no ordinary meal and soon we’re in the realm of something like a dark fairy tale or folktale that’s real but slightly underlit, strange, full of desire, fear, and expectancy. As I say above, this particular story is informed by “The Fisherman and his Wife,” which concerns the dangers of wish fulfilment.

By the way, marriage is one institution that is easily destroyed by those who refuse (or are simply too tired) to remain attentive to the wonder around or in front of them—usually the wonder of their partner, whom they think they know. Could art save marriages? Probably not. But you might give it a try by reading The Flounder. How’s that for a sales pitch?

JR: Excellent, I’ll alert all my friends in bad marriages! Now, before publishing The Flounder with Blackwater, you published two other collections, The Animal Girl (LSU), Retribution (Picador), and the novel More Than Enough (Picador). Why do you seem to lean towards the short story as a form?

JF: For whatever reason, the form of the story is more intuitive to me. Perhaps I’m better at compression than expansion. I also like the way stories use implication, expressive absences and silence. What’s not on the page can be just as important and expressive as what it is on the page. Novels do this, too. But a short story, by its nature, almost necessarily does it.

I’m also dyslexic, which makes many things challenging for me, including the English language. I have issues with spacial relations and easily get lost, even in my own city of Boston. The novel can feel vast and my process of writing one often involves charts, outlines, sticky notes, drawings, and various other methods of reminding myself of what came before so that I can see what might come next. On the other hand, the story fits more easily in my mind as a unity. As a reader, I love both short fiction and novels. But there is a uniquely intense and immediate pleasure in reading a story in one sitting that just isn’t possible with the novel. Finally, the psychic toll of writing a novel is considerable. The great short story writer Lorrie Moore compares a story to a love affair and the novel to a long, hard marriage. As any practicing writer knows, there’s no guarantee that any project will succeed. I’ve published one novel but have begun many more and have two full drafts of two different novels in the drawer. I’ve also written or begun countless unsuccessful short stories. A failed short story may sting for a day or two or even week, after which you regroup and start another one.

JR: You’ve touched on how the stories in The Flounder are set across several countries: America, France, Hungary, Switzerland. Tell us a little bit about that, and about how you find the setting for each story?

JF: As I say above, I lived in continental Europe for four years in the early 1990s, which was an intense time for me. I learned a new language, was living in a new culture, and was reflective and self-conscious about what it meant to be American in an increasingly global, shrinking, and complex world. That was thirty years ago. The material resisted narrative fiction until the pandemic started and I was living in Europe again. The first story I completed about this time in my life was “Budapest,” about a Mormon kid from rural Utah discovering Eastern Europe shortly after the Berlin wall falls. He’s trying to escape from his own conservative and restrictive background just as the city dwellers around him are beginning to enjoy their own newfound freedom.

While I’m not a Mormon, I did grow up in the rural western United States, which is often defined by conservative religion and conservative values. It’s also an immense place and not easy to escape, which was one of the reasons I decided to leave it. I was aware of and reading many writers who’d felt that they had to leave their homeplaces to do their work: Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, and many more. “Budapest” is very much about this: leaving cultural and familial ideas of the self behind and seeing whatever you might see once these are gone or exposed for what they are. Of course, the character in “Budapest” also discovers that it’s almost impossible to escape the mythology of the United States, which I discovered, too. There’s a love-hate relationship the world has with the U.S. for good reasons. But it’s the adoration for the U.S. and its media culture that dogged me and that dogs the poor kid in “Budapest,” whom everyone recognizes immediately as American when he simply wants to fade away and lose this part of his identity. It turns out that it’s very hard to start over. Even Americans, who believe in the notion of self-making, have to live with history.

But I also write about the places I left. The story “Saved,” about two kids who befriend an elderly neighbor, takes place in the Mohave Desert in California, in a small town where I lived for a number of years as a kid. I know that town just as I know the Bible-belting church where the two kids go every Sunday. There’s a loneliness to that landscape that I absorbed and that, I hope, becomes expressive in the story. All the other places in The Flounder—Chicago, Boston, Normandy, Switzerland, Budapest—are places I spent time in or even lived in. I feel the same way about setting, a home or a room or a store or a hotel. Knowing the layout of rooms can help me make a setting feel real and fully evoked on the page. While I’ve never been robbed in a pawnshop, my grandfather used to own one. As a kid I spent a lot of Saturday afternoons with him behind the counter. He’d been robbed many times and he told stories about it. He died decades ago, but I hope I captured something about him in “Box of Watches.”

JR: The names in The Flounder are interesting. Daren and Martine in “Lovers.” Daniel and Marian in “Nocturne” and “The Flounder.” There’s something unsettling about it.

JF: Names are deeply personal and, I think, magical. They literally summon or call forth a person. That’s why we often say them. While some people know why they choose certain names for their children—i.e., their namesakes are beloved friends or relatives—often one is attracted to the sound, the impression, something mysterious in the cadence or syllables that, for whatever reason, seems right. If the name of a character doesn’t fit, I feel distracted by that and tend to grind to a halt until I find the name that works. I really can’t say why those characters ended up being Daren and Martine, Daniel and Marian. Martine, I knew, was from a French-speaking culture and I like the sound of that short, sweet “i” in the final syllable. I wonder if you’ve ever had a friend or acquaintance whose name just didn’t seem to fit them for whatever reason. There’s a cognitive dissonance when any given Frank, Jane, or Myrtle just doesn’t seem like a Frank, a Jane, or a Myrtle. What if Hamlet had been, I don’t know, Romeo or, to really stretch it, Frank…? There are so many great characters from literature—Holden Caufield, Huckleberry Finn, Julien Sorrel, Emma Bovary, Dorothea Brooke. To put it another way: character is spectral, hard to contain and embody, and names do just that—they hold and reflect character.

JR: That’s funny you mention that: sometimes I’m not sure the name John fits you! But perhaps that’s because it’s so close to home…

JS: Yes, I’d say the same about you. Of course, our name suffers from overuse. There are so many Johns out there that we’re in danger of being seen as part of a generic group. So perhaps we’re both too unique for our name?

JR: There are various themes that crop up in this collection and in your work generally, some of which we’ve mentioned. Nicholas Delbanco wrote on The Flounder: “Marital fidelity and infidelity are at issue here, as is the relation between generations and the search for (one might as well call it) authenticity.” One could say the collection also comments on love and loss, old age, poverty and wealth. How much does an author choose what they write about? Is it a conscious decision to have these themes reappear in your writing?

JS: Many years ago, the novelist Alice McDermott read a few chapters of a project I was working on and suggested a different direction. I started to explain what I wanted to do with the project and she said, with some vehemence, “Forget about what you want to do. You don’t choose your material. Your material chooses you.” I think the reason her words have stayed with me is that, in my experience, they’re true. I don’t think too much about theme or what my work is about. I think about character, about development (I don’t want to be repetitive), about surprising the reader and myself, creating tension, syntax, diction, tone, and avoiding cliché. But my material tends to be whatever bothers me, eats away at me, nags at me, and begs to be told or given expression to. There’s often a silence or void at the center of the thing I’m working on—something that needs to be said and that maybe can’t fully be said or explained—that tends to gain force as I work, that pulls words out and around it and suggests the next word or phrase or scene. That’s when I’m in what I’ve heard a lot of people call the “zone.” You don’t want to get in your way then by overthinking a story. You follow your gut. You keep going.

JR: Do you have a favourite character in The Flounder?

JF: I hesitate to admit that I do have a favorite character, but I think I do. It would be Kent Boyd in the story “What Kent Boyd Had.” I grew up with a lot of men like him. He’s cocky, loud, masculine, lacking in emotional intelligence, and more oblivious to those around him than he should be. While I probably wouldn’t want to have a beer with him, I think that I succeed (I hope I do) in making him sympathetic. I put incomplete versions of that story away for weeks and months only to take it out again and find it interesting. I kept seeing different sides of him and learning more about him as I worked. That’s what kept the story going for me and, I hope, what will make him and his story interesting and moving to readers. He’s as vulnerable as he is blustery. While he makes stupid mistakes, they reveal flaws and needs that give him dimension, depth, and, I hope, humanity.

JR: Let’s zoom in a little: what makes a good sentence to you? By and large, your writing feels quite measured, composed – it doesn’t seem as though there’s any rush to get this story out. How do you see the relationship between plot and language?

JF: Great question. I like surprises in my sentences, something jolting, a small explosion, a word or phrase that shimmers just a bit. Of course, there are different variants or degrees of stylized prose. Some writers veer towards transparency (I mostly do) and others toward linguistic pyrotechnics. Both are great if done well. One stylist I’ve appreciated over the years is the English novelist Martin Amis, whom we just lost recently. Here are some great sentences of his on the art of novel writing: “The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity. Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are either predictable or sensationalistic. And it’s always the same beginning, and the same ending.” There’s so much intelligence and wit in this prose. Who else would use a phrase like “ineluctably trite” or “violently uneven”? And the way he describes “life” from the novelist’s point of few is brilliantly defamiliarizing. He says nothing we don’t already know about the subject. But he says it in a way that makes what we know new to us.

As for the relationship between plot and language, I think this is mostly contained in the prose rhythms, in syntax and diction. Plot isn’t that interesting, though it does create tension and stakes, and it should rise organically out of the language. When I’m writing, I pay close attention to each word or phrase I put down because these suggest the next word or phrase. The cadence of the opening sentences to “Box of Watches” is explosive. We sense that we’re in the middle of a hold up before we see the gun. On the other hand, the opening sentences to “Budapest” are quieter, the rhythms contain an expectancy but not violence. We’re not surprised to feel and see that this story about a voyage is finally a romance and concerns a developing intimacy and connection between two people who meet on a train and spend the next few days together in a city that is strange to them.

JR: 100 words, biggest influences?

JF: You can’t escape your background, your religion (even if you lose your faith), your childhood, the landscape you grew up in (the western US), and then the choices you make as an adult, which involve where you live and what you do. All that is in my fiction. The writers who shape me change every year. But here are some: early Denis Johnson, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, early Richard Ford, William Trevor, the wacky and brilliant Joy Williams, Tim O’Brien, the sentences of Richard Brautigan, and often the last really good story collection or novel that I’ve read.

JR: Finally, you teach in the MFA writing programme at University of Massachusetts Boston. How do you enjoy teaching? Is it helpful for your writing?

JF: I love teaching, especially when the writing isn’t flowing. I have a ready-made community of like-minded folks among my colleagues and students, all of whom care about literature, reading, and writing. That’s invaluable in a culture that is often indifferent towards art. But teaching is a full-time job and tends to require most of my energy when I’m doing it. While I can get some work done during the academic year, it can be a struggle. Even if I have the time to work, the energy can be lacking. I do a lot of my writing during breaks and during the summers. It’s a gift to be on an academic schedule, which allows for long periods of concentrated work. Otherwise, seeing my students develop as writers and publish their work is exciting. I love that. It can prod me on to the next project, the next unforeseen story or novel.

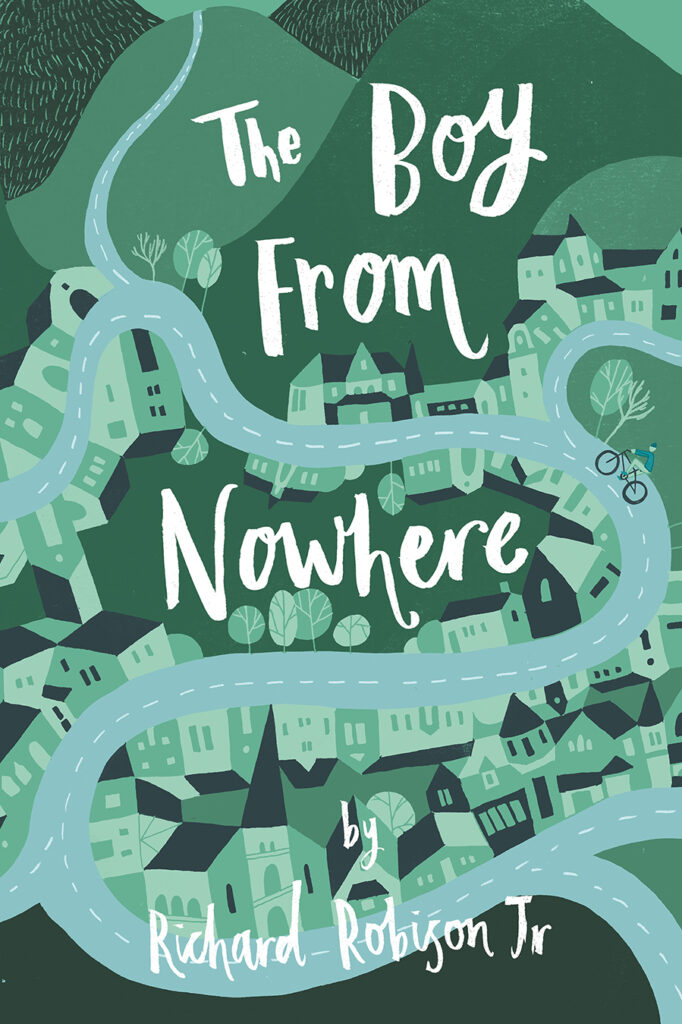

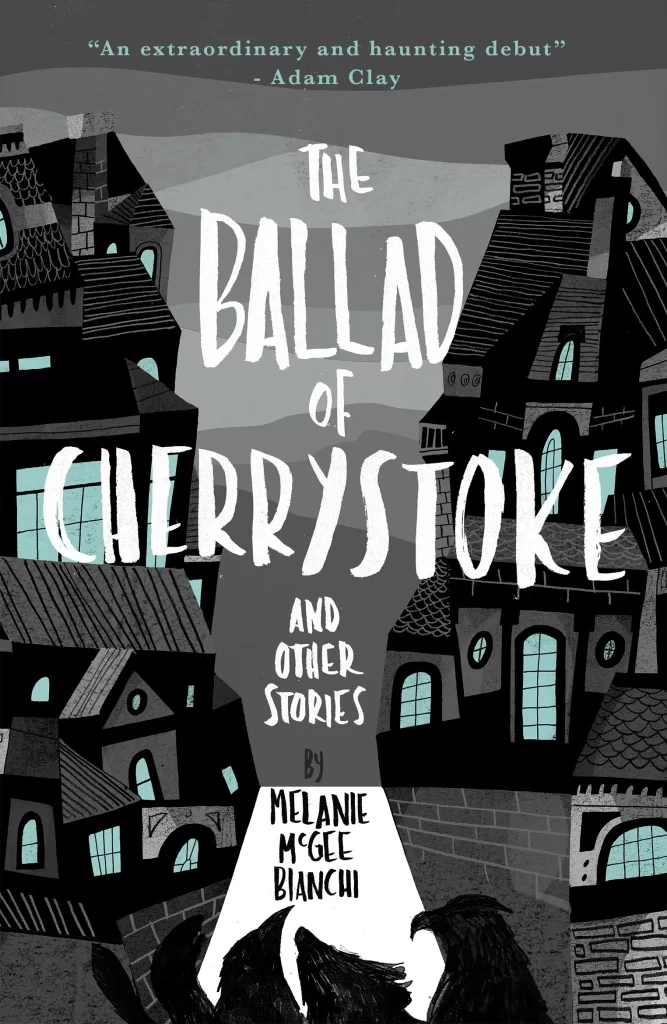

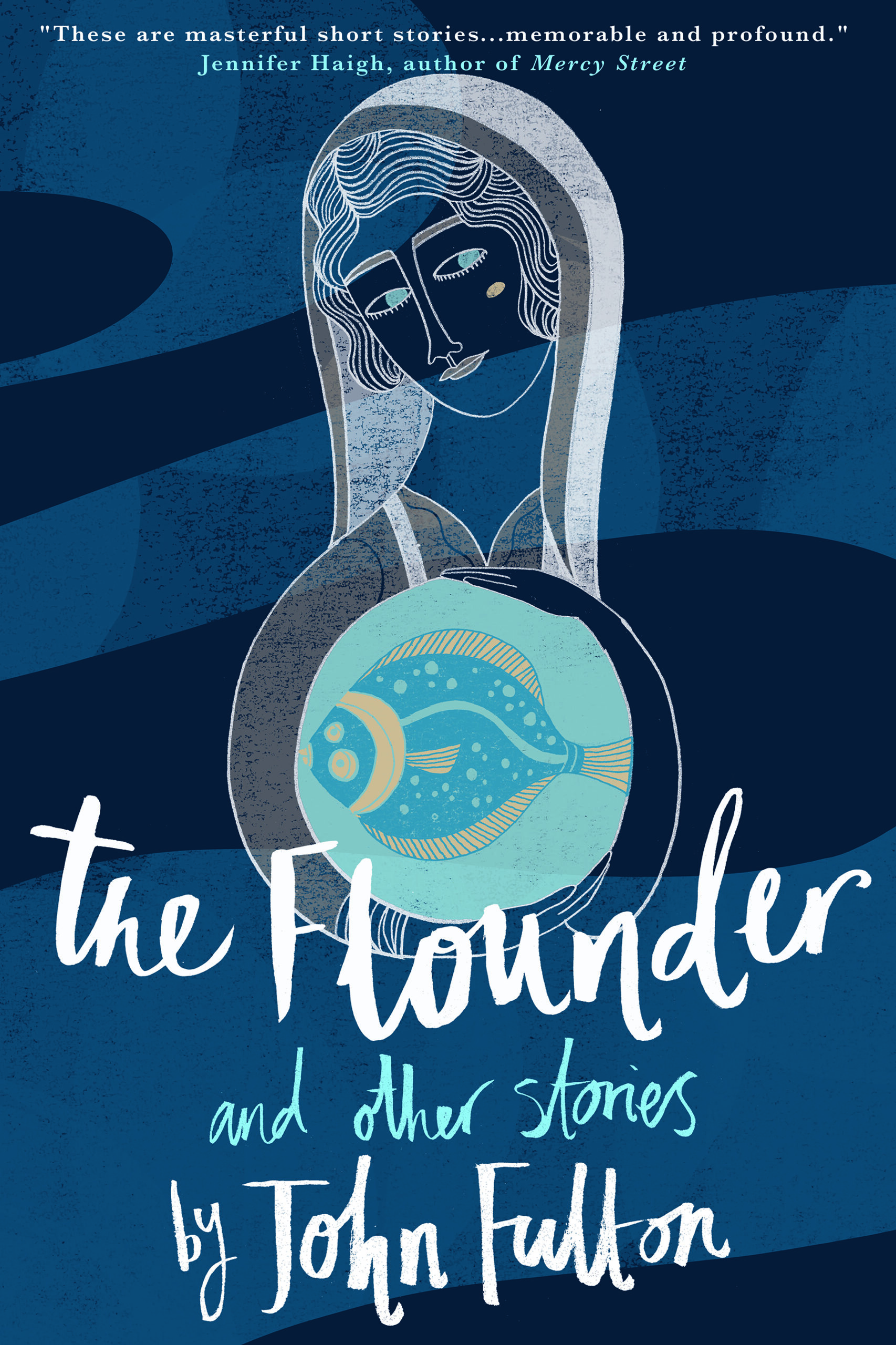

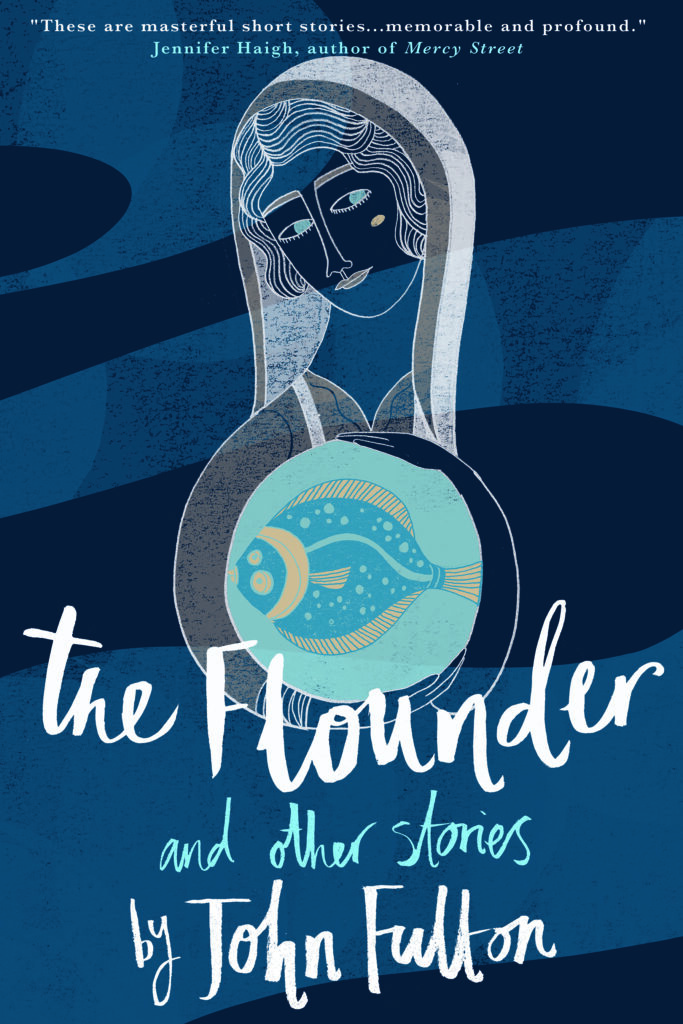

The Flounder

by John Fulton

Publication date: 27th of May 2023

The riddles of desire, youth, old age, poverty, and wealth are laid bare in this radiant collection from a master of the form. From inner-city pawnshops to high-powered law firms, from the desert …

$9.99 – $18.99Toxic Positivity Afloat: a Modern-Day retelling of Hemingway’s The Old Man and The Sea

Toxic positivity is running amok, and not even Hemingway’s Santiago can reel it in. Then again, reeling it in would be the antithesis to Santiago’s indestructible pride just as it would be to a large percentage of humanity whose hold is as relentless as the old man’s. Some would label it a conundrum; others, a paradox. And both would be challenged. Destruction is a much better word choice. And yet even if Santiago could turn back the clock, his toxic positivity (i.e., his unshakeable perseverance and determination) would prevent him from charting a different course. Santiago would, most assuredly, resist even the known dangers that led to his eventual downfall.

Toxic positivity brings with it a level of denial and minimization of such dire consequences that is reminiscent of the inevitability Santiago encounters as he attempts to bring in his giant marlin, knowing full well that the sharks are gathering. And yet, he takes pride in pressing on. He denies that one plus one equals—will always equal—two. Toxic positivity would argue otherwise, even with the facts clearly stacked.

Even as Santiago encountered one defeat after another, both from the uncertain and incalculable seas to his physical and mental exhaustion, he held tightest not to the pain from the skiff’s ropes, but to his own toxic positivity. And if Santiago were to magically appear among us in 2023, he would be welcomed with opened arms by throngs of those who have also become drunk on the sugary concoction that they gulp by the gallons. Metaphorically, this modern-day retelling represents toxic positivity through Santiago’s unnerving denial as those of us who become its victims struggle, much like the marlin, to remain afloat in turbulent seas that circle us like the unwelcomed sharks, knowing full well the outcome. Donning a falsely-positive façade leads nowhere except a manic search for an abundance of fig leaves. In the end, our fate, like Santiago’s is sealed, leaving toxic positivity like a thin, barely-visible layer of ice covering depths of the sea that we do not wish to traverse, however lightly. Toxic positivity’s first cousin, avoidance, has nowhere safe to rest its weary body.

Oh how I wish Santiago’s fragile feelings of doubt and grief and aloneness could have been shouted to the rooftops, soaring into the gathering clouds, where he could absorb the rushing storms to then gaze upon the emerging sun. Shaming and guilt and failure be damned. Unfortunately, Santiago does not recognize his own self-inflicted cruelty, anymore than we do. That’s the real tragedy. “Santiago,” I would whisper, “it’s okay to not be okay.”

Kathleen M. Jacobs writes books for young readers. She holds an M. A. in Humanistic Studies, and lives in Charleston, West Virginia. She can be reached at www.kathleenmjacobs.com

A Q&A with Patrick Colm Hogan

JR: A People Without Shame is a strange book, full of contrasting parts. At times diary, at times legend, at times transcript, at times article, it seems as though the novel is trying to demonstrate how difficult it is to convey its subject matter in a conventional manner. What do you think of this interpretation?

PCH: Yes, that seems to me right. I didn’t think of it in precisely those terms, but I agree. Perhaps surprisingly, I thought of it more from the reader’s side than from the author’s. Specifically, we are always given only diverse and fragmentary sources, with necessarily partial and to some degree biased construals of events. Then we have to figure out what happened, relying on somewhat opaque and surprisingly malleable testimonies of limited reliability. Actually, this is the case even from the author’s perspective, and even if the work is itself testimonial. Specifically, empirical research has shown that our memories of events alter with the circumstances in which they are recalled. In that sense, even someone who experienced the actual events has to puzzle out—as if from blurry photographs and recordings distorted by static––what really happened.

JR: Yes, with several of the events mentioned in the book there is no way to truly know what happened, due to the opacity, and due to bias and misinformation. It’s nice that we don’t see that anymore these days, isn’t it?

PCH: Despite the ellipses, problematic chains of transmission, etc., I actually think we end up with a pretty solid idea of most major events in the novel (though, as you say, there are some that remain bewildering). For example, our initial information about Songari prisons is basically hearsay. But when A. ends up in a Songari cell, there are enough confirmatory details to indicate that the “hearsay” is well-founded. Also, A. is not omniscient and he does have biases (like everybody). But, in my view, he merits our trust in both his general competence and good intentions. Sometimes a postmodern writer will suggest that we cannot ever really get at the truth (or, what is more extreme, that maybe there is no such thing as the truth). I wanted to indicate that, despite difficulties, this is not the case. Most often, we can get a good idea of the truth—though, in evaluating the evidence, alternative explanations, and so on, we need to be aware of the very serious problems we face (again, even with our own personal experiences).

JR: You have dedicated much of your life to studying colonialism, and until now have chiefly written scholarly non-fiction on the subject (as well as many others). After authoring over twenty academic books, what motivated you to take the plunge into fiction?

PCH: Actually, things happened in the opposite direction. I was writing poetry from 7th grade on. In 1972, as a freshman in high school, I won a poetry contest in Kansas City, announced at an event which featured a reading by Mona van Duyn (later to become a poet laureate of the United States) and earning myself the royal sum of $25 (apparently equivalent to $181.44 today). It is worth noting that it was an anti-war poem (A People Without Shame is, perhaps before all else, an anti-war novel). Twenty-five years later, perhaps unconsciously emboldened by this early approbation, I wrote a book-length, narrative poem, based on Hindu goddess myths. I had no success in publishing it until 2014. While trying to publish that, I wrote and repeatedly revised A People Without Shame. I had much more success with scholarly writing, which led me to devote my time and effort to that. Even so, the two types of writing have remained inter-connected for me. For example, later this year, Routledge will publish my most recent scholarly book, What is Colonialism?, which derives in part from my work finishing up A People Without Shame for Blackwater. Indeed, the critical book in some ways (indirectly) explains what I am doing in the novel.

JR: And what did you spend your $25 on?

PCH: Probably LPs—The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Grateful Dead; the sorts of things other kids my age were buying. If I bought poetry, it would have been e. e. cummings.

JR: From where in particular did you draw your influences when you were creating Somota, and when penning the epic of Garuna that is woven through the book? When A. arrives and introduces us to it, it feels like a very real place.

PCH: Thanks. The sense of reality (insofar as people do indeed feel that) probably has two sources. First, the main characters and the things they do have sources in my own, biographical experiences. Though I re-imagine them in a very different context (something that our minds have evolved to do pretty well), I feel that the original motives, beliefs, rationalizations, and so forth, remain plausible in the new circumstances. Second, I have tried to push myself to give considerable detail, thereby making the places, events, and people more distinct and particular in the reader’s imagination (or “simulation,” as cognitive scientists would say). This tends to foster a sense of reality in part by fostering an emotional response.

As to influences, those are of two types—historical and literary––which also (I hope) contribute to the sense of reality. As to the former, I have sought to base most of the particular occurrences in the novel on historical precedents. Examples range from the missing generation of Somotan men (derived from the radical reduction in men of the draftee generation in the U.S.S.R., due to German colonialism), to the preoccupation with hunger (due to a range of colonial policies that have consistently rendered colonized societies food insecure), to the nature of the conquest of Somota (which is modelled on the conquest of Igboland), to some aspects of the insurgency (which are based on actions of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army). More complex structures also have historical sources. For example, the broad organization of the region by reference to the northern Songari, the south-western Kelans, and the south-eastern Somotans is modelled on Nigeria, with the Hausa-Fulani to the north, the Yoruba to the south-west, and the Igbo to the south-east.

As to the literary sources, people will probably remark most readily on the use of the Mahabharata in The Dream of Garuna, with the five ruling brothers, the disenfranchised eldest brother, and so on. But I draw almost as much on Exodus, with the abandonment of Garuna in the river to his leading his people out of the land of their bondage. I draw also on a range of myths ranging from the puranas of India to the oral tales of the Americas, sometimes as recounted in Levi-Strauss’s magisterial multi-volume Mythologiques. I was surprised to be reminded of the relevance of the story of Sin and Death, when I had to re-read Paradise Lost recently. When I listened to an audiobook of Vergil, I was also surprised to see the recurring influence of the Aeneid on the treatment of war in the novel. There are no doubt many other, forgotten influences of this sort. Modern works have of course had an impact as well. I have often emphasized Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians. Joyce’s Ulysses is a more subtle, but pervasive presence.

JR: In saying you pushed yourself to give considerable detail so as to foster a sense of reality in the reader’s imagination by fostering an emotional response, you make storytelling sound quite formulaic. Is it?

PCH: Well, it is in part formulaic. I’ve argued (in, for example, What Literature Teaches Us About Emotion) that emotional elicitors are not a matter of broad evaluation, but of concrete perception or imagination. That has partially formulaic consequences, but only partially. Here’s a simple example. Someone might write a story about a first date, including the statement, “We went to a restaurant and had something to eat.” For a particular story, this might be the most appropriate thing to write. But it would probably be better to develop some details in the vast majority of cases. Contrast the preceding, generic statement with deciding to forego the restaurant when the two of you see a popsicle stand, then—on reading the available flavors––puzzle over just what is a boysenberry is, or the two of you go to the restaurant, but end up only sharing a dessert, due to the scandalous prices. There isn’t a single right way of doing this for every story, and sometimes writers will make disruptive blunders in trying to be particular, thereby breaking the emotional continuity of the piece and undermining the effect. But, for the most part, such particularity is, I believe, more likely to foster engagement, emotional response, and a sense of reality.

JR: Kehinta is a compelling character. How would you describe her to those who haven’t read the book?

PCH: She is the Somotan bard in charge of preserving the main oral epic and of refashioning it to serve the social and political needs of her society. But, like other Somotans, she also does manual labor—fishing, when she is in a traditional, Somotan community. Unlike our stereotype of a poet, or our gender stereotypes, she is not at all romantic. She works with A, not for the wonders of poetry—still less from some exaggerated respect for Europeans in general or A. in particular––but for the medical supplies he arranges in payment. She has a pragmatic, non-moral response to sexuality (though, of course, she despises force or coercion in sexual relations). On the other hand, she is almost certainly more vulnerable than she appears. That discrepancy is mainly due to the fact that she hardly ever shows weakness. Like a traditional Igbo man (such as Okonkwo in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart), she will fairly readily express anger, but only hints at sorrow or fear. Those moments come, for example, when she alludes to her husband’s death, or when she becomes concerned, however briefly, that A. has set her up to be an informant. This isn’t a cultural trait, by the way, but an individual trait. For example, the other woman who is assaulted in the novel reacts with great fear and sorrow.

JR: For how long had the novel been in the works? Did any particular parts come first?

PCH: About 25 years. At this distance, I can’t recall what I wrote first and what came after. I do remember that I did a lot of “scholarly” background work to guide the writing. For example, I outlined out some principles of the Somotan and Kelan languages (both imagined as Indo-European languages) in contrast with Songari (a Semitic language). I also sketched a more detailed geography. I don’t know where any of those notes might be now; I probably discarded them.

JR: We must discuss your protagonist A., and the difficult themes the book addresses. A. often laments that he is in a painful position. He is keenly aware of his status as part of the colonial regime, disparaging of the Reverend G. and the government’s mission, and frequently faces discrimination himself. Yet, he is simultaneously too afraid to do much of anything about the injustices surrounding him. And of course, when compared to the people of Somota, who face the destruction of their culture and the massacre of their communities before his eyes, the reader is keenly aware that he is really not in such a painful position at all. What do you think of A.? Do you like him? He doesn’t seem to like himself very much.

PCH: Somotan traditions (in the novel) suggest that the more ethically sensitive one is, thus the more moral one is, the more keenly one is conscious of one’s sinfulness. I think A. is a very humane character and he does act with genuine moral courage. But he is deeply aware of just how little he has tried to do, the times when he has not tried to do anything at all (as in the case of the Kelan weavers), and how ineffective he has been even when he has tried to do something. His first problem is that he is naïve. But he is open to learning and does learn, if incompletely. Moreover, he does face real dangers. First, there is the possibility of continuing imprisonment, with all that suggests about his future. Then there are the implied dangers to Kehinta, suggested by G. It is also critically important that there is no clear social context in which he can join with others in shared anti-colonial work. Such a context is necessary if anyone is going to accomplish anything positive, whether against colonialism or any other social harm.

JR: And a comment on the discrimination A. himself faces. He is Jewish, and Irish, among predominantly English fellows – correct? What motivated this character background?

PCH: Well, the Irish part is me. (I did one of those genetic tests a couple of years ago and it claimed that something like 90% of my genetic ancestors came from Clare or Cork; evidently, we didn’t travel much.) This allowed me to talk about the anti-colonialism in my extended family, basically just attributing it to A.’s background. The Jewish half is due in part to my mother’s repeated claim that, if she weren’t Catholic, she’d be Jewish. I briefly misunderstood this as a child, but soon came to realize that it was just her hyperbolic way of saying that she would never be a Protestant. Much more importantly, I wanted A. to have some more direct experience of personal discrimination. His Irish background gives him a connection with social poverty and the like, but he does not experience much personal discrimination, except perhaps from other Irish characters.

JR: Have you or will you ever write anything else based in Somota?

PCH: I had never thought about it, but on reading your question, I immediately thought that it would be possible to write a work about, say, two linguists, one Somotan, one European, who are working on the language in independent Kela; the European, upon reading A People Without Shame, begins to suspect that his colleague is Kehinta’s daughter. That would probably never be resolved. This story might be intercut with news reports or Kelan television ads, or something else rather different from the translations in A People Without Shame. I think it might work. But my health probably won’t allow me to undertake such a project.

JR: What books have you read that influenced how A People Without Shame has turned out?

PCH: I’ve already mentioned a number of them. I might add works on colonialism, especially in Southeast Asia and Central and South America. Indeed, though the colonialists in the novel are British, the concerns that drove the writing of the novel were far more about U.S. imperialism in, for example, Guatemala or Chile. (This reminds me that the novel is also influenced by cinema, such as Costa-Gavras’s Missing and Z.)

I should also add works on ethics, both various of Kant’s writings and work on dharma theory in Hindu tradition. A recurring theme in Somotan culture in the novel—a theme that I’m afraid might readily lend itself to misinterpretation—is that the moral quality of an act is not reflected in the benefits of its outcome for the agent. Somotan ethics is, so to speak, the diametric opposite of prosperity theology. For example, what happens to Kahngee in no way suggests that what she did was wrong.

JR: A word on the epic of Garuna, and the various other myths and folktales scattered throughout the book. How did you find the shift between writing in this style, and writing from the point of view of A.?

PCH: I have written fairly many imitations of different styles over the years. It wasn’t to train myself, but just for fun. A few were part of academic articles. They were sometimes imitations of chapter styles in Ulysses. They were sometimes other things—for example, Nabokov’s Pale Fire or the speech of some public figure, such as Joe Biden. As a result of this (inadvertent) practice, I found it easier to switch styles than it might have been otherwise.

JR: Finally, looking back on the book now, is there anything in there that surprises you, that you did not expect to feature in a book published with your name on it?

PCH: There are certainly things that would have surprised younger me. But I drafted the book long enough ago that what is there does not surprise me now. I am a bit surprised that I seem to have left out most of the embarrassing errors that were present in earlier versions. That is due, in part, to your careful readings, as well as those of Elizabeth and Vivien.

JR: Agreed, we deserve all the credit…

PCH: Actually, the three of you do deserve the credit of seeing value in the book, so that it has been “published with [my] name on it.”

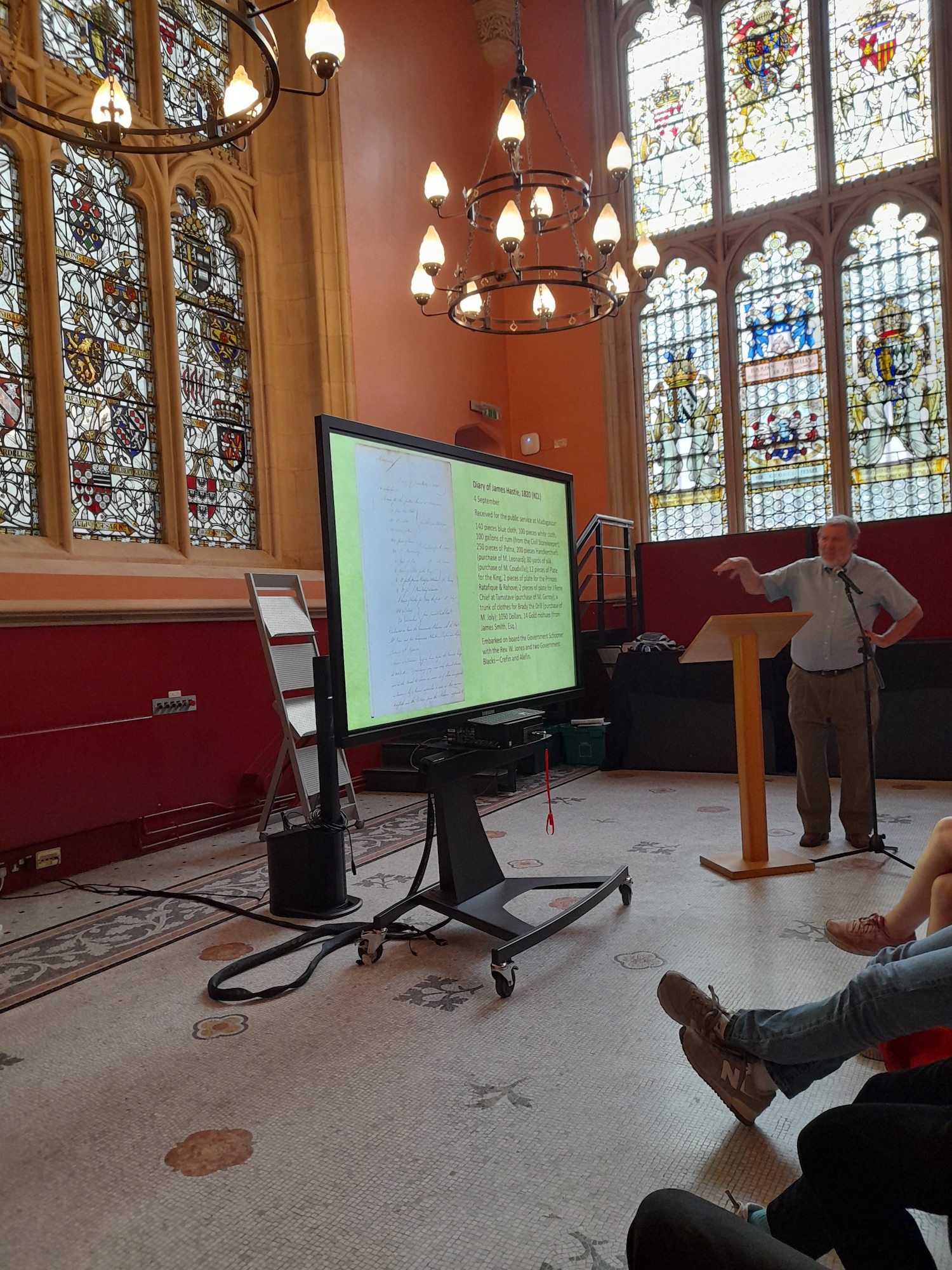

Mission to Madagascar: The Sergeant, the King, and the Slave Trade

by David H Mould

In 1817, a decade after Britain banned the slave trade to its colonies, a 30-year-old East India Company sergeant with no diplomatic training embarked on a risky mission. James Hastie travelled for almost a month from the coast of Madagascar through the tropical rainforest to the central highlands. His mission—to persuade Radama, the young and warlike ruler of the most powerful kingdom on the island, to stop the export of slaves.

Most studies of the slave trade focus on the transatlantic traffic to the United States, the Caribbean and South America. Yet for hundreds of years, a larger trade flourished in the Indian Ocean where Arab traders trafficked their human cargoes from East Africa to the slave markets of Arabia and India.

From Madagascar, slaves were smuggled to the plantations of Mauritius, seized by Britain from France during the Napoleonic Wars. Its governor, the subtle, silver-tongued Robert Townsend Farquhar, was in a tough position, under pressure from London to end the slave trade yet knowing that the island’s economy depended on slave labor. Without the ships to police the sea lanes, he decided that the best strategy was a diplomatic one—to form an alliance with the rising military power in Madagascar.

The relationship between Hastie and Radama would shape the course of history in the southwest Indian Ocean. Hastie lived by his wits as he won the king’s confidence. The intelligent, charming yet ruthless Radama skillfully used the British envoy to assert power over the nobility and his political rivals who profited from the slave trade.

The treaty they forged was a deal with the devil: in return for the slave trade ban, the British trained Radama’s army and supplied muskets and gunpowder, allowing the king to expand his dominions, while turning a blind eye to the internal slave trade. Hastie became the British agent in Madagascar, and a trusted advisor to Radama, accompanying him on his military campaigns and introducing social reforms, until his untimely death in 1826.

Mission to Madagascar is based on Hastie’s unpublished journals, one of them recently discovered, and other primary sources, including letters and political and military dispatches. The journals from 1817 to 1825, archived in Mauritius, London, and the U.S., weave a narrative of hazardous travel, byzantine court intrigue and colonial geopolitics, and offer the most comprehensive early 19th century account of Madagascar, its landscape, crops, industry, commerce, culture, and inhabitants.

David became fascinated by Madagascar’s history and culture after making five trips between 2014 and 2017 for a UNICEF research project. Unable to travel for more than two years because of COVID, he decided he wanted to tell someone else’s travel story. He describes his research on Hastie as “like a large jigsaw puzzle, where the pieces never exactly fit” but ultimately “a thrilling and rewarding historical journey.” This is the first biography of a man whom Sir Mervyn Brown, a former UK ambassador and historian of Madagascar, described as “one of the most important and attractive figures in the history of Anglo-Malagasy relations.”