Your basket is currently empty!

Category: Newsletter

The importance of reviews for small businesses

We are always very grateful for our readers – both of our books, and of our newsletter. It’s tough to emerge in such a congested field, where competition is fierce and where publishing is, for better or worse, accessible to everyone.

Blackwater is small but feisty, and we wouldn’t be here without you all. If you follow us, it’s because you believe in our ethics, in the quality of our books, in independent publishing being the alternative to the choral voice of the mainstream. It’s thanks to readers like you that we exist, and thrive.

We are well aware of the world we live in, though, and it’s a world where the loudest are heard, and the flashiest are seen. It’s not easy to build user relationship when there are so many competitors and alternatives demanding attention.

How can we gain credibility? Well, a big part is played by reviews. Think about it: if you have to buy…anything, say a saucepan, or a jumper; or if you have to choose a restaurant, which do you pick? The ones with lots of positive reviews, or the one with only a few (or, even worse, lots of negative reviews)? We know the answer to that, and it’s only natural. Apparently between 92 and 98% of users take online opinions into consideration to help establish their own. And we understand that!

But aside from helping others choose their next read, reviews are important because they bump up the business SEOs. Plainly put: user-generated content helps the business’ online presence remain relevant and fresh, so that if you’re looking, for example, for a book about recent Irish history, our own While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us by Boni Thompson will come up in the top results. Imagine you’re looking online for something, and you type the words in the search engine: how many pages will you click on before you start deeming the rest of the results less relevant? Not many, and that’s all SEO doings.

So, if you have a moment, please consider leaving reviews for your local shop, your small business owners…or your favourite independent publisher – hint hint, wink wink! On any platform: our own website, Amazon, Goodreads, social media…anywhere. It means a lot to us, and it really helps us grow and stay afloat in a shark-infested waters.

Pre-orders Galore!

We know our latest news has been quite unsettling, and I’m sure it has given our gentle readers much food for thought.

But the show must go on…and what better way to celebrate the future of the publishing world than a bunch of exciting new books available for pre-order?

First up, The Three Lives of St Ciarán, by Spanish queer fiction author Inés G. Labarta.

This book, my friends, is not for the faint-hearted. An experimental tripartite narration that delves deep into three very different dystopian scenarios, and dramatically different writing styles – from modern to epic to future – to bring to life three different versions of Saint Ciarán, to restore hope, faith, and brightness for humankind.

Next we have Loveland: a Memoir of Romance and Fiction, by Susan Ostrov. Do not be fooled by the title: do we look like the kind of press that publishes the book equivalent of candyfloss? We thought not. Blackwater candyfloss will always come fortified with nourishing substance. The backbone of this memoir is literature: the books we read shape our reality, and the author relates her personal romantic experiences to her perceptions of her reads, and their critical apparatus, discovering her true self relationship after relationship. And book after book.

Finally, Burying Norma Jeane, by Leah Rogin. An on-the-road story that combines a deep understanding of the life and filmography of Marilyn Monroe (Norma Jeane), with a mother-daughter relationship under the timeless strains of the approach of the teenage phase that takes them both by surprise. All three women navigate the challenges of femininity, to a cathartic, liberating end.

Which will be your next read?

The Supply Chain

Dear Readers,

On Thursday, our North American distributor, Small Press Distribution, announced that it had filed bankruptcy and ceased operations. We had no warning, or inclination at all, and our collective reaction can best be described as !!&*))@0@WTF))*(2 SPD….!!)__

Moving on. Why should you, gentle reader, care? Distribution and the supply chain are admittedly the least-sexy aspects of being a publisher, but still, important. And even without reference to Elizabeth’s powerpoint presentation on book distribution in North America, important to the general reader.

Here’s a Cliff’s Notes version: no one buys books from the publisher. Books go from publisher to distributor to wholesaler to shop. Shops like to support small presses and other small businesses, but at the end of the day also like to write one check. We can’t blame them; bookkeeping is hard. Hence book distributors, to do all the things we can’t do because of basic resources of time and manpower. Bookshop. Amazon (ahem. Not that any of us would ever use that for books…). Shops.

Again, what’s this have to do with you? A great deal. The closure of SPD will have a major and lasting impact on literary culture in the United States. We’re considering a number of solutions that will make us stronger, but we will never be able to compete with the big publishers. So, the best things you, our family of readers can do, is continue to support us by purchasing directly, leave reviews of our books on major sites (Goodreads, Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes and Noble, etc…) and, please, encourage your locally owned small bookshops to stock our titles and be in touch directly with us at sales [at] blackwaterpress.com.

This news only affects the US supply chain, and Elizabeth has plenty of copies of all titles on hand, but the same is true for the UK/Europe: please put your local shops in touch with Luca.

We thank you for your ongoing support.

Resurgemus.

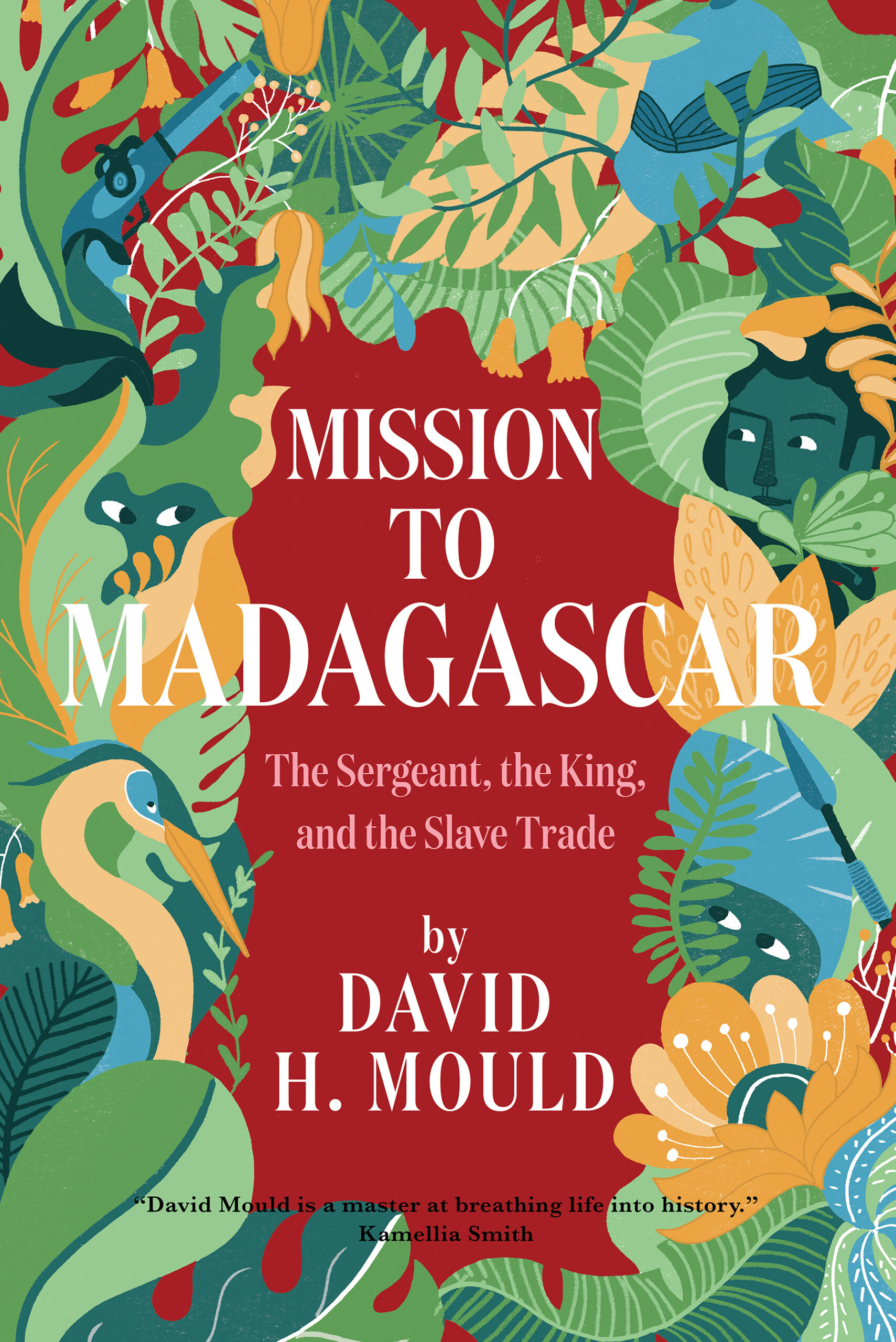

Black History Month: Mission to Madagascar

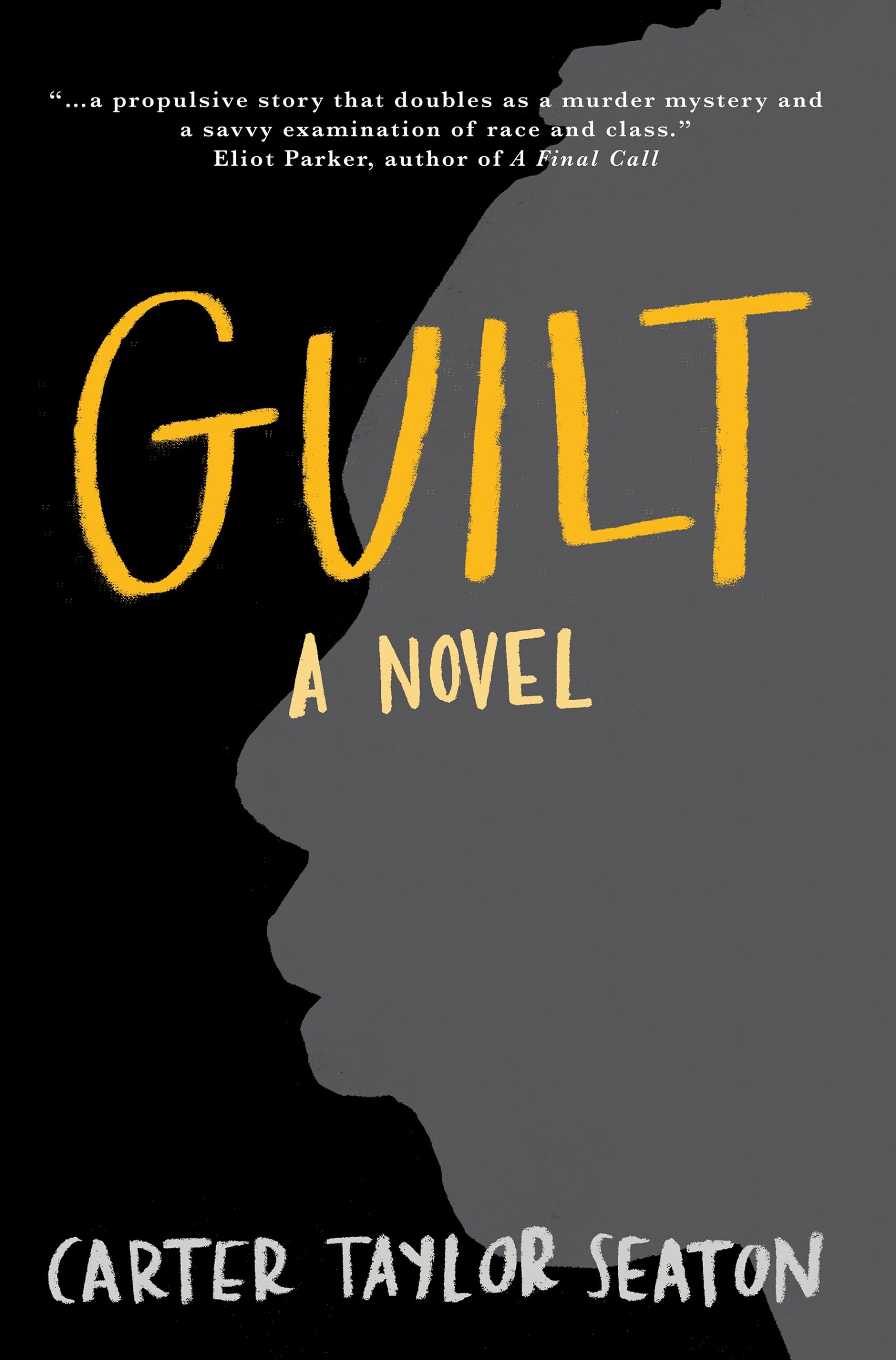

The month, we’re donating 25% of proceeds from sales of Guilt and Mission to Madagascar to Charleston’s Keep Your Faith Corporation. In this blog post, author David H. Mould explores the history of slavery in the British Empire.

Black History Month has given me reason to reflect on the history of slavery in Britain, the country where I was born and lived until my late twenties.

Recently, the legacy of slavery and the issue of reparations to descendants of slaves has become a major topic of public and political debate. Universities, museums and corporations have been critically re-examining their own histories. Were their founders or benefactors slaveowners? Or did they, like the merchants and shipowners of London, Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, benefit indirectly through transporting slaves or the products of plantations? What is their modern-day responsibility for the acts of the past?

Universities have established slavery research centers and grants for graduate students from communities of color, corporations have invested in diversity and community development programs. Statues of leading citizens connected to the slave trade have come tumbling down. Descendants of former slaveowners have come forward to offer apologies and, in some cases, financial restitution.

Most of this history was new to me. If anything about Britain’s slave trade and plantation economies was in the school curriculum in the 1960s, it was buried under the weight of all those kings, queens, prime ministers, battles, treaties and acts of parliament whose deeds and misdeeds I had to regurgitate on tests.

For centuries, the major colonial powers—the British, French, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese—had engaged in an expanding slave trade from Africa to supply labor for their plantation colonies in the Caribbean and South America. In every country there was opposition to slavery on moral grounds, but economic interests always prevailed.

In 1794, in a radical social reform by France’s new revolutionary regime, slavery was abolished. However, it was impossible to enforce the ban in the Caribbean colonies, where plantation owners threatened to secede to Britain where slavery was still legal. Slaves in Haiti rebelled and overthrew the French regime, but slavery remained in France’s other Caribbean colonies.

After a long and well-financed campaign from the abolitionist movement, Britain became the first colonial power to ban the slave trade by act of parliament in 1807. The act did nothing to help those who were already enslaved. Economic interests again prevailed: to abolish slavery without importing a new labor force to the plantations would have spelled financial disaster, both for the owners and for Britain’s commercial and financial markets.

It was more than a quarter century later, in 1834, that Britain abolished slavery in its colonies. For most slaves, “freedom” was a technical change in legal status; most became indentured laborers and saw little improvement in their living conditions. And the slaveowners were handsomely reimbursed for what was called their “loss of property.”

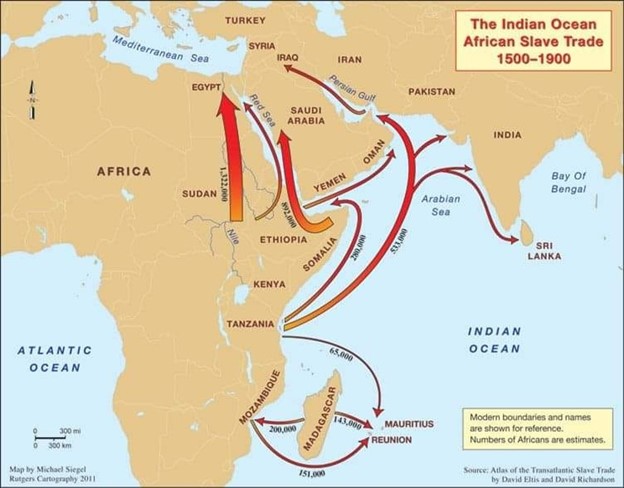

Map caption: Source: Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Ellis and David Richardson (Yale University Press, 2010) When British and Americans think about the slave trade, they naturally focus on the transatlantic traffic from Africa to the Americas—to the United States, the Caribbean, and South America. It was not until I began research for Mission to Madagascar: The Sergeant, the King, and the Slave Trade that I began to understand that the slave trade was a global phenomenon.

Slavery had existed in African societies for thousands of years. People, especially those without a family to protect them, were bought, sold, exchanged, or used to settle a debt. Captives taken in wars between tribes were ransomed to their relatives. Then the Arab traders arrived on the east coast of Africa and turned the local slave trade into an international business, with established supply routes and lines of credit for commercial goods to purchase slaves.

The traders found willing partners in the tribes of the heavily populated Great Lakes region, a vast area that now comprises parts of western Kenya and Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Malawi, and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Tribes raided villages, seizing men, women, and children. They exchanged them for the currency of the period—cloth goods imported from India, brass wire, beads, muskets, and gunpowder. With their guns, they took territory from weaker tribes and seized their cattle. When the supply of war captives dried up, they would find a pretext to start a new conflict.

The traders assembled caravans of up to 1,000 slaves to march hundreds of miles to the coast, with bands of armed tribesmen to protect them from raids by local tribes. The traffic in slaves went hand in hand with the lucrative ivory trade, with male slaves carrying huge elephant tusks. The main entrepot was the island of Zanzibar, ruled by a dynasty from the Arabian Peninsula. From Zanzibar, their dhows carried slaves north to the markets of Arabia, Persia and India.

Southeast of Zanzibar, the plantation economies of the islands of Mauritius and Bourbon (today Réunion) in the southwest Indian Ocean were completely dependent on slave labor. Where did the slaves come from? Most were shipped from the island of Madagascar.

For centuries, warring clans had stolen cattle and taken war captives, who were ransomed to their families or kept as slaves. The arrival of French slave traders in the 18th century opened a new and lucrative market for captives. On the northwest coast, Arab traders shipped slaves captured in the interior across the Mozambique Channel. Some were marched to slave markets in the central highlands or to east coast ports for shipment to Mauritius and Bourbon, others sent north to Zanzibar.

Mission to Madagascar, based on primary sources, recounts an almost forgotten chapter in the history of the global slave trade. Without enough naval ships to patrol the seas to stop smuggling, or the troops to mount an invasion, the governor of Mauritius, seized from the French during the Napoleonic Wars, opted for a diplomatic strategy. He decided to try to persuade Radama, the young, impetuous and warlike ruler of the rising military power in the island, to conclude a treaty to halt the export of slaves.

James Hastie The unlikely hero of the story is James Hastie, a 30-year-old East India Company sergeant with no diplomatic experience, dispatched in 1817 to travel to Radama’s court. His journals recount how he used his wits and persuasive powers to win over the king who faced strong opposition from nobles, army commanders and clan chieftains who profited from the sale of slaves.

The treaty ending the slave trade from Madagascar came at a price. Just as the British government later compensated the plantation owners of the Caribbean for their “loss of property,” the governor agreed to recompense Radama for his loss. The British trained his army, provided him with the muskets and gunpowder he needed to subdue rival clans, and recognized him as king of the whole island.

The moral victory of ending the slave trade was tempered by political and economic expediency. Britain secured a powerful ally, kept the French out of Madagascar and gained favorable tariffs for its trading ships. Meanwhile, the internal slave trade in Madagascar continued unabated.

Rebel Cork

The Easter Rising of 1916 was one of the major events of the twentieth century that changed the map of Europe. Following a week of violence centered in Dublin, the men who led the fight were arrested and shot at Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin. The British hoped this was the end of the rebellion; it was just the beginning.

Our first book of 2024 is While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us by Boni Thompson, based on her grandfather’s time as a significant part of the 1st Cork Brigade of the IRA during the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921). Read on for how Dr. Thompson combined family history, memoir, and archival research for a gripping and harrowing account of James Fitzgerald’s work for an independent Ireland.

Boni Thompson The story of my grandfather, James, has been a long time coming. Partly because back in the 1990s when I started to research in earnest, (not so long ago, but definitely a pre-find everything-on-the-internet world), finding any new information about the Irish War of Independence here in Canada, information that was not hagiography, or hero worship, was nigh impossible. I knew I would have to go to Ireland, to Cork, to Dublin, and various university libraries, beg for access to rare and unique documents locked up behind closed doors, and do the research myself. Afterall, nobody that I could see was talking about any of the details of that war save a few well-known escapades. It was as if a few educated men, such as Éamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith, and a few secretive intelligence men like Michael Collins made the whole thing happen by magic. I knew by the stories my grandfather had told me that this was far from the truth. Since an extended stay in Ireland was out of the question, especially with a young family in tow, I shelved the whole project before it was even started.

A few years later, on a fine autumn afternoon, I was driving home listening to CBC radio, and over the airwaves a Canadian academic from Newfoundland was introduced, by the name of Peter Hart. When the title of his book was read out, The IRA and its enemies: Violence and Community in Cork, 1916-1923, I slowed down and turned up the volume. When the interview was over, I drove straight to my local bookstore and put in my order. I was excited to hear that somebody, and a Canadian no less, was writing about the many people in Cork, James’ contemporaries, who were involved in that terrible struggle. And not only that, he was writing about the clashes between the status quo and those who would destroy it, about the violence, about the widespread nature of the conflict and he certainly didn’t sugar coat the bloody details. I fully expected James to be mentioned. He was not.

What was mentioned, however, were versions of stories, versions I didn’t recognize, men’s actions described, violence categorized and tabled, but their stories missing. These men had their actions documented, but they were somehow detached from the context in which they lived their daily lives, overseen by occupiers from another country and of another race. They were described as engaging in sectarianism, concerned with religion or class of those they fought. These versions of men, young and old, did not mesh with my own version of my grandfather nor any of the friends, fellow IRA members, or the commanding officers that he had spoken of to me, with sadness, with respect, sometimes with humour and a chuckle. The short, and it is true, sanitized tales that he shared with me when I visited him always clearly communicated one specific thing: They were fighting to get back their country, in their own hands, a fight carried on from distant generations.

They faced before them a dangerous, treacherous enemy; an enemy manned with guns and weapons that were outlawed to Irishmen, men who represented a foreign king, who manned his gaols and his dungeons and his workhouses, and who would not go quietly from that island, nor would they willingly leave behind them over 700 years of administration, of fine homes and castles, of cheap labor and lucrative business and agriculture, all while many Irish suffered poverty, lack of education, lack of rights to their own language and culture, lack of opportunity for themselves and their children. This was the enemy they faced and it would take nothing less than courage, imagination, determination, resilience and yes, sometimes cruelty, in order to be successful and drive the enemy off their island, back where they came from.

In the end of course, they did it, and a high price they paid, those men who, like James, perpetrated acts of violence in the name of freedom. Some got tangled up in violence and were changed irrevocably because of it. Others were able to walk away, reconstitute themselves as law abiding citizens. I do believe however, the vast majority of them suffered, some their whole lives long. They suffered because their worldview did not include acts of intentional violence; acts that were clearly crossing lines, lines that had been drawn for them from time immemorial. However, it seems to me, they did what they felt they had to do, no more, no less, and even as the fight got worse, more terrible than they could have imagined, they kept on.

The Irish have them to thank, now, 100 years later, a prosperous nation, free of occupation, of greedy overlords, and foreign masters. I believe it is this fact, the fact that their actions contributed to winning freedom for the nation, that allowed them to return to a normal life, despite being haunted by their youths. A life where their children had opportunities they could never have dreamed of in their own youths, because of that freedom, so hard won.

It was not easy to write my grandfather’s story. He was most definitely an insider in the centre of Cork, very close to the command structure of the IRA. The men he worked with and for understood what it meant to be an Irish Rebel fighting for their country, and the depth of resolve it took to stay with the fight, despite hardship, danger, and threats to family. This common connection with a secret knowledge of each other and what each was capable of bound them tightly together in their common task, so tightly some would suffer under torture and death before divulging information of each other. It was hard to read of kidnappings and executions, harder still to write of him participating in them. But his words stayed with me at such times, that he was a soldier of Ireland, fighting a foreign enemy, and given the history of Ireland, an often cruel and heartless one. He saw his compatriots as like-minded, trustworthy, mostly good men, strong men, doing what they believed had to be done, despite the offensive nature of some of their tasks.

The violence perpetrated by the IRA, much of it reactionary, is only a small part of the story. The way they are portrayed in academic work, gave me the impetus to tell my grandfather’s story differently, in contrast. That is, I had to tell the larger story, the context of his life and times, from his point of view, in order to see how he saw and feel how he felt in order to act in the ways he and his compatriots did. I tried to write of those historic years, 1916-1923 in Cork in such a way that his world is made apparent to us. I wanted to be true to the facts as they stand, but also, light had to be shed on the inner lives of James and his colleagues in order to have a chance at revealing the world in which those young men and women lived, their own bubble of time and place.

I did not know how I could do this without much more information. A librarian at the National Library of Ireland suggested posting an advertisement in the Cork paper. It seemed like a crazy idea to me… after all, this was the late 1990s and James had left us 10 ten years earlier at the age of 92. But in only a few short weeks, I found in my mailbox a lovely letter from a man whose mother had grown up a few doors down from James. She remembered the family well, but not James. She did mention that the younger brother had blown off his fingertips making bombs. Such a fabulous detail to build a story on! I was delighted and grateful. I wrote letters to distant relatives who had been children when James was in his 20s and 30s. They told me the hard truth. He was a difficult man in those years. I brooded on this information.

It was not until I found the newly launched compendium of witness statements posted by the Irish government after 2000 that suddenly telling his story seemed possible. I was disappointed to discover that he himself did not leave a statement, or if he did it was not included. There were however descriptions of actions taken where he was present, mentions of his attachment to headquarters, the intelligence squad, the active service unit, even the day he was shot in the head and taken to Victoria Barracks. This was exactly what I needed, but still not enough to write a full story, a story that was truly authentic and thorough.

I called up a professor at University College Cork history department. A kind and generous man, he knew of James and advised me to apply for his pension application. That took what seemed like forever, two years and two phone calls to the Irish civil department responsible. On the phone the woman in charge apologized for the delay. She said that some applications may never be made public because of the sensitive nature of the disclosures made therein. She suggested that James’s application was such a one. Shortly thereafter it arrived, a fat package of photocopied documents, letters from his old friends, some, at the time men in high places, recommending him for an officer’s pension, scolding the bureaucracy for taking so long in their deliberations. But the document that made his story possible was the list of actions that he undertook, written in his own hand, all verified by witnesses. It is a long list.

By this time, of course, the age of the internet was up and running, and so with this document I sat down and created a timeline of events, where he fit in, who he worked with, what was in the newspapers that day or evening, even the weather conditions, and tried through each event to see inside his world, indeed inside his head. From a carefree 17-year-old at the time of the Easter Rising through to the tough, hardened young man of 25 years old, who after watching beloved leaders and good friends alike suffer and die, kept the faith through it all.

I will say that this is something I still do not truly grasp, despite almost three years researching and writing about James, my grandfather. The rebel spirit in defence of a nation, of an ideal of freedom, a spirit that will not die, will not succumb, will not be cowed or broken or bought. Winston Churchill famously once said, “We have always found the Irish quite odd. They refuse to be English.” And later when speaking of the Irish Free State Act, asked the rhetorical question, “How much have we suffered in all these generations from this continued hostility?” Such statements could only be pronounced by victors, wishing to hide their culpability and reframe their guilt. We forgive Churchill, having led the world in the fight against the great evil that was Nazism, never giving up or giving in, hanging on with dogged tenacity despite setback after setback and a fierce, terrifying, enemy. Perhaps Churchill had learned something more from the Irish then what he proclaimed. Perhaps we have more to thank Irish rebels for than we realize.

While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us is already available as e-book on our web site, and pre-orders for print copies are open; publication date is March 17. We also offer an e-book + paperback bundle at a special price! To secure yours, just select ‘bundle’ in the drop-down ‘edition’ menu on our website.

And here’s some musical accompaniment that should make you want to sign up for the IRA.

Black History Month: Guilt

To honor Black History Month, we’re donating 25 percent of proceeds from sale of Guilt and Mission to Madagascar to Charleston’s Keep Your Faith Corporation, a Black-led community youth literacy, mental health, workforce development, and food access program. We’re featuring a guest blog post by Carter Taylor Seaton on the inspiration behind her latest novel Guilt.

In my hometown, Huntington, West Virginia, city workers are busy hanging 150 banners on the downtown light poles to honor our African American citizens who have made a significant contribution to the city, state, or nation. It’s one of the city’s way of recognizing Black History Month. It’s no wonder we do this—Huntington is the birthplace of Carter G. Woodson, well-known as the Father of Black History. For years, we’ve commemorated the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. with a march, speeches, church services, and solemn celebrations, but the banners are a relatively new addition.

As I watch the banners go up, I can’t help but think of the cities where such an honor would probably go unnoticed. And of the young African Americans whose lives were either cut short by violence or who have served sentences for which they were wrongly incarcerated. To date, the Innocence Project has freed over 200 wrongly convicted persons, most of whom were from communities of color where policing tends to be heavier.

This is the background against which I wrote my latest novel, Guilt, (Blackwater Press, 2023) although it’s not wholly about the guilt or innocence of a young Black man. It’s more about the guilt felt a young boy who knew a detail about the crime that might have exonerated the defendant. Despite his close friendship with the accused’s brother, the protagonist says nothing. For that he suffers guilt the rest of his life.

The synopsis on the back cover says, “Judge Alexander Betts has carried the burden of guilt most of his life. Now a bench trial before him forces him to finally deal with the reasons behind it. In Southern Georgia in the 1960s, Alexander knew something about the murder his best friend’s brother was accused of, but he kept silent. Now, faced with an anonymous threatening letter, and a case with similar circumstantial evidence, he wants to set things right. Will he finally find the courage he lacked at sixteen?”

Why did I, a septuagenarian white female, choose to write about a Black sixteen-year-old boy? And to use his voice, making him the narrator of many chapters? Simple—because the story intrigued me, especially as I watched the Black Lives Matter movement grow. You see, I’d had a second cousin who, in the 1960s, had unsuccessfully defended a young man of color who’d been accused of a capital crime. In our family, he was a hero despite his inability to win the case.

As I watched beating after shooting after questionable arrest blast cross the television screen, I thought of my relative and realized there was the nugget of a novel that wanted to be written. I knew better than to “write to the market,” as they say but felt the issue of racism wasn’t going away anytime soon and that feeling guilty was an eternal, universal emotion.

About the same time, I was reading The Kite Runner by Kaled Hosseini. Here was a story set in Afghanistan about two boys: one a victim; the other the silent witness to that victimization. This novel helped to inspire the form of my story.

Once the story began to grow in my mind, I knew I needed to do some research even though I wasn’t writing a non-fiction piece. Although my cousin, who’d been the defendant’s lawyer in the actual case was dead, his son remembered the story, so I interviewed him. I also interviewed the son’s good friend because he had known the defendant. And I researched actual case notes from murder trials of the 1960s. Now I had the bare bones of a story. After recalling the form of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, I knew how I wanted to narrate it—in the voices of those involved.

For me, novels aren’t simply retelling of an incident. They have to have a deeper point. Sticking to the “bare bones” facts is also unimportant. So, I moved the story south, and created the narrator whose life is changed by what he knows but doesn’t tell. I’d grown up during segregation and knew what that had been like, but from my perspective, not the Black community’s. Still, I recalled railing against it when my father wanted to take my brother out of the newly integrated high school. I’d been a bit of a teenage rebel, listening to a Black radio station from Gallatin, Tennessee, that played what my parents classed as “filthy Negro music” and attending Black rock and roll concerts in defiance of my parents. Additionally, because I’d lived in the South for ten years, I felt I could infuse the story with its flavor, its feel, its culture, the language. I began with enthusiasm.

Then I read American Dirt, the novel by Jeanine Cummins that came out in 2018, and began following the controversy surrounding it. Cummins is an American woman but she wrote the story in the voice of a Mexican mother who flees her home with her child in search of safety on American dirt after a drug cartel kills most of her family. Cummins was given a seven-figure advance when women of color were facing roadblocks when trying to tell their own stories. The cry arose: “She has no right to tell our story. Who does she think she is? That’s cultural appropriation.” Admittedly, some esteemed Latinix writers applauded the novel but the term stuck. Suddenly those of us who dared to imagine stories other than our own got nervous. Who was I to try to put myself in the shoes of a sixteen-year-old-Black kid?

Yes, I’d lived in the deep south for ten years. Yes, I’d worked with African Americans at nearly every turn in my career and was familiar with the sound of the language and the dialect of the south. And yes, I knew code-switching often came easily to most African Americans at some point in their lives. Code-switching is adopting standard English in gatherings where African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) would perhaps make the speaker sound uneducated despite their background. One gal I worked with was a master at it. I could tell when she answered the phone whether or not she was speaking to friends or family or to a white business colleague.

I spoke with a couple of fellow authors, some Black, and decided to follow the advice of Colson Whitehead: “Tackle the story that you’re scared to begin; that you don’t know if you can pull off.” I dove into it. I wrote chapters narrated by the protagonist, Xander Betts; chapters narrated by the defendant’s attorney, Gerald Baxter; chapters narrated by the defendant, Leon Pepper; chapters told by a third person narrator; and one, which I ultimately discarded, by the dead victim, Miz Annie Sowards.

As I wrote, I shared my growing stack of chapters with friends in two writing groups. While fascinated with the story and applauding its pace, there were mixed reactions to the language. “It’s too much dialect. I can’t read it,” said one. “There’s not enough distinction between the white and Black voices,” said another, after I’d toned down the dialect. I was ready to tear my hair out.

Eventually, I called on a friend for help. A member of my book club, she’s African American, a retired professor of English at Marshall University and an expert in AAVE. Thank goodness for Dolores. Although she felt I could realistically use more AAVE, together we compromised on just how much was enough—enough to give the voices distinction but not so much that it was difficult to read. All in all, I completely rewrote the book three times over the five years it took to complete it.

When the book hit the bookshelves, with glowing blurbs from advance readers, the spate of stories about Black deaths at the hands of perhaps over-zealous police had subsided, overtaken by the war in Ukraine, Donald Trump’s legal woes, and the heating up of the upcoming 2024 presidential election. For that I’m delighted although it doesn’t mean incidents don’t still occur. Reading Guilt may remind you of our country’s struggle with racism as much as celebrating Black History Month reminds us of how far we’ve come. But maybe, just maybe, one year we should hoist banners commemorating those young Black lives like Leon’s.

Interview with Flora

April 25, 2021: Spring Hill Cemetery Park, Charleston, West Virginia. Elizabeth was walking her collie, Sally, when Sally came to an abrupt halt. A loud meow was echoing from the woodpile at the bottom of the hill. People organized and dogs were passed around and a friend scrambled over the bank where a small black and white kitten emerged, yowled loudly, and was carried up the hill and passed to Elizabeth. Because of an edict from our attorney, the kitten was only supposed to be staying until the animal shelter reopened on Tuesday, but by then it was too late. The kitten, knowing a good deal when she saw one, got to work quickly. With an evident flair for literature, she quickly turned into an essential Blackwater Press team member and chose her first manuscript (Ma Chere Maman…), she demonstrated total disdain for dogs Sally and Lucy, and made her nest in any and all available laps. This was before she had demonstrated her prowess as a killer.

For Answer Your Cat’s Questions Day, we’re delighted that our very own Flora MacDonald Ford agreed to sit down and answer some of our questions, based on the set used by many authors for character development that originated in 1890 with Marcel Proust.

- What is your idea of perfect happiness?

I am perfectly happy. - What is your greatest fear?

Being homeless again. Being hungry again. - What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?

Nothing. I’m perfect. - What is the trait you most deplore in others?

Weakness of character and lack of purpose. - Which living person do you most admire?

Mommy. - What is your greatest extravagance?

Liberty print collars from Made by Cleo. I have my eye on a chicken-shaped cat bed, but I’d probably just look at it and never get in it… - What is your current state of mind?

Pensive. There are birds outside the kitchen window. But I can’t get them. Otherwise content. - What is hardest about your life?

What I think most people don’t understand is the constant pressure. It’s just one thing after another, and the constant demands. It’s all very complicated, and no one really knows what it’s like. - What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

Niceness. - On what occasion do you lie?

Never. - Describe your role at Blackwater Press.

As official kitten, I like to think I play a key part in the publication process as well as the day-to-day running of things. - What do you most dislike about your appearance?

Nothing: I’m beautiful. - Describe your average day.

I like to be up early: between 4 and 5 most mornings, and I get my breakfast immediately. After that I’m shut out of the bedroom because not everyone appreciates the joys of the morning like I do. I like to run around and make noise, sit in the kitchen sink and watch birds, guard my litter box, and sometimes I’ll get fish on a stick and drag him around for company. Around 7 or so I’ll start howling at the bedroom door. When it finally opens, I run around and show my tummy. Then there’s more bird watching until it’s finally time for morning tea and laptime. Then I like to help make the bed. I think it’s an important part of the daily routine. Then depending, I either nap, play, help with work, or look out windows until lunch. After a hectic morning, I sleep most of the afternoon. Locations vary. Around 5 I like to wake up and run around, maybe play with gnome on a stick, have a drink, and then have my dinner. Then it’s back to sleep until about 8, then I move and sleep on the back of the couch or have more laptime until bedtime. I like to play before bedtime, and sometimes get a snack. Most days follow this schedule with some variations depending on location and schedule. - Which living person do you most despise?

He knows who he is. - What is the quality you most like in a man?

Long legs make the best lap. - What is the quality you most like in a woman?

Softness. - Charles Edward Stuart’s famous escape across the Highlands following his army’s crushing and ignominious defeat a Culloden: discuss.

Thanks for this question. I must say that dressing a very tall man who needed a shave and didn’t speak the local language as a woman to smuggle him out of the country isn’t the best idea I’ve ever heard, but apparently it worked. And passing him off as Irish. What’s that say about mid-eighteenth-century perceptions of Irish women? They were big, ungainly, and homely? - Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

MEEEROWWOOWWRR - What or who is the greatest love of your life?

Mommy. - When and where were you happiest?

I’m happy when I’m baking at the heat duct behind the kitchen door at home, teasing Sally, and having my tummy rubbed. Or when Mommy is holding me. I like to be held.

- If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

Nothing. I’m perfect. - How do you pick manuscripts?

It’s all down to how the paper feels on my butt. That instantly tells me the quality of the work. - What do you consider your greatest achievement?

I’m only three but those who keep count say I’ve killed 26 varmints of various descriptions. - What is your most treasured possession?

My Fish on a Stick. - What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

Going to the veterinarian. - What is your favorite occupation?

Snuggling. Playing. Killing. Teasing Sally. Looking out the windows. Climbing my cat tree. - What is your most marked characteristic?

I have the strength of my convictions. - Who are your favorite writers?

Elizabeth Auld, Zoe Strachan, William Burleson, John Fulton, Melanie Bianchi, Robert Ford. - Which historical figure do you most identify with?

Flora MacDonald (duh?) - Would you kill the Blackwater Bird?

No comment (shows tummy). - What is it that you most dislike?

The veterinarian. - What is your greatest regret?

There was that time I had to have some help finishing off a mouse. I’m so embarrassed. The Angel of Death requires no assistance. - Why are you so cute?

(rolls over, shows tummy) - What sort of music do you like?

Can I tell you what I don’t like? I don’t like live baroque flute. It hurts my ears and makes me attack the player. And there was that time Mommy had the job interview in Colonial Williamsburg and had to play fife. We don’t talk about that. I also know as a figure of some historical importance I feature prominently in many songs and tunes. I don’t mind some of them, like “Flora MacDonald’s Farewell to the Prince,” or “Flora MacDonald’s Fancy,” but some are just insipid. “Tweedside.” What beauties doth Flora disclose? How sweet are her smiles upon Tweed? Please. And don’t get me started on the “Skye Boat Song.” - What is your motto?

Can I have two?

Nemo me impune lacessit.

Tha fios aig an luch nach ‘eil an cat a’s tigh.

- What is your idea of perfect happiness?

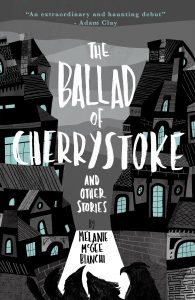

Short Story Day 2023

December 21 is the shortest day of the year – and it’s no coincidence that it’s also Short Story Day! Short stories are becoming increasingly popular. With their variety of plots, settings, and characters, they are bite-size reads most people can wedge into busy schedules, or even enjoy in one sitting to savour different scenarios.

Have you read any of our short story collections? We’d like to spend a few words about our short story authors and their wonderful books.

Aside from our Short Story Contest, which we ran for two years and had us come in contact with some excellent authors (debut and expert), we published Melanie McGee Bianchi’s The Ballad of Cherrystoke and Other Stories (2022) – her first published short story collection, and ours too, so a double first! Melanie’s essays have been published regionally and nationally, and her poetry has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and her essay on ballads appeared in the 2023 winter issue of Oxford American. The Ballad of Cherrystoke is deeply rooted in the area that has shaped her character: Appalachia. It explores gentrification and culture clash in the mountainous South, where the beauties of the natural landscape meet a complicated contemporaneity. Her dry, earthy prose tells the stories of the area’s everyday people. For all these reasons, it was an SPD Bestseller!

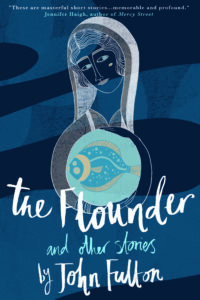

The second short story collection we published is John Fulton’s The Flounder and Other Stories (2023). John’s short fiction has been awarded the Pushcart Prize, cited for distinction in The Best American Short Stories, and published in a variety of journals and reviews. His other books have received several distinctions and prizes. The Flounder explores the riddles of desire, youth, old age, poverty, and wealth. From pawnshops to law firms, from California to the coast of France, it lays bare the complexities and poignancy present in everyday life, in a prose that is vibrant and lyrical. The Flounder was chosen for Poets & Writers New and Noteworthy Books Section, and selected for SPD Recommends.

For 2024, we have a new short story collection in the pipeline: Khanh Ha’s The Eunuch’s Daughter & Stories. We are very excited to have Khanh Ha on board at Blackwater Press. As well as winning our second Blackwater Press short story contest, he is a ten-time Pushcart nominee, finalist for The Ohio State University Fiction Collection Prize, Mary McCarthy Prize, Many Voices Project, to name but a few.

Khanh Ha He has published several books and short stories, and has been awarded the Sand Hills Prize for Best Fiction, The Robert Watson Literary Prize in Fiction, The Orison Anthology Award for Fiction, and many more. His exploration of modern and olden-day Vietnam will lead you into imperial palaces populated with concubines and eunuchs, riverboats where a stranger consigns his past into a little girl’s hands by gifting her a myra bird; through war zones and bombarded villages, and cosmopolitan households where lies and truths form a web that questions moral standards.

Will you be choosing short stories for your holiday reads?

October 2023

And here it is, the end of the month again. October has seen the publication of Carter Taylor Seaton’s novel Guilt, with events with our friends at Booktenders and Plot Twist, the WV Book Festival, and events for Mission to Madagascar at the Kanawha County Public Library and Booktenders.

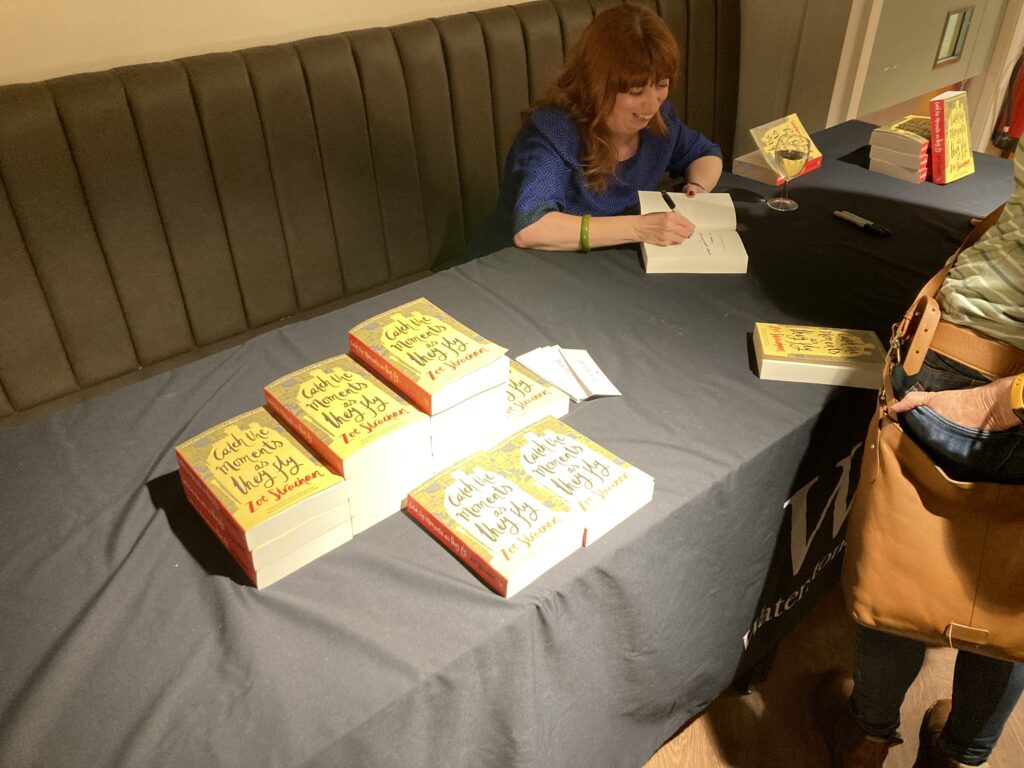

Zoë Strachan also continued to celebrate the launch of Catch the Moments as They Fly in style, with more wonderful events at Golden Hare Bookshop in Edinburgh and the Dick Institute. Also check out Zoë’s interview on BBC’s The Afternoon Show.

A blowhard at WV Bookfest called Elizabeth sweetheart, and told her words don’t sell. She corrected him to Dr Sweetheart.

We just passed National Cat Day. Why not celebrate with a copy of R. R. Davis’s The Various Stages of a Garden Well-Kept?

Our last book of the year is the wonderful and deeply unsettling novella Symbiosis, by Milagros Lasarte.

And, we end with the announcement that our co-founder, John Reid, has left the company to start a new life in Mexico. We thank him for his years of dedication and vision, and wish him all the best in his future plans.

September 2023

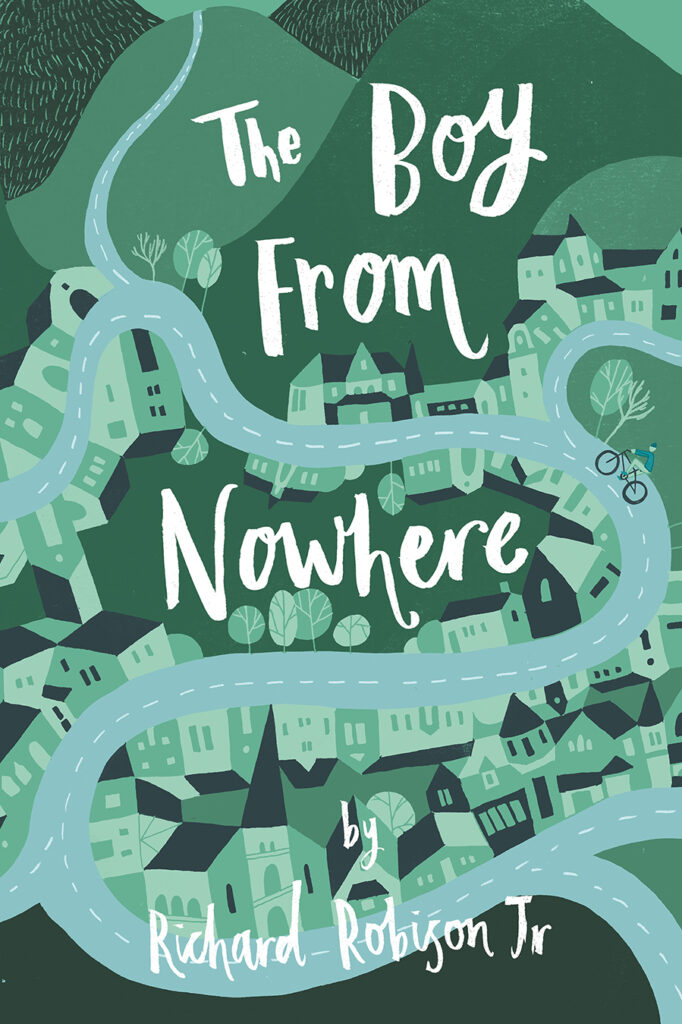

Look at that, our newsletter this month falls on publication day for Richard Robison’s gorgeous memoir: The Boy from Nowhere!

“The Boy from Nowhere surprised the heck out of me…Offered with modesty and narrative grace, charged with heart-stopping events and characters.”

– Stephanie Marlis, National Endowment for the Arts recipient, author of Rife.

The Boy from Nowhere

For young Richard, every year it’s the same story: as soon as he settles into his surroundings, with its friendships, school, sports teams, and all those customs that make a place home, he is forced to move. As a boy who is wiser beyond his years, he sees his parents’ strain to follow the upwardly mobile quest of the American Dream – but at what cost? This memoir reveals what it was like to be a teenager in 1960s America. It is a book about disconnection and loss, but also of hope and change: the person we once were does not dictate the person we will become. This recognition is what ultimately holds our destiny.$9.99 – $23.99September also saw the launch of Zoë Strachan’s novel Catch the Moments as They Fly. We can’t thank everyone enough for coming to the launch event at Waterstones in Glasgow on the 21st of September, and so glad to hear how much folk are enjoying the book!

And we have more book celebrations coming up, so we’ll round off by listing our October events. Hope to see you at some of them – wherever you are in the world!

5th October – Mission to Madagascar with David Mould (US – Athens)

12th October – Catch the Moments as They Fly with Zoë Strachan (UK – Edinburgh)

14th October – Catch the Moments as They Fly with Zoë Strachan (UK – Kilmarnock)

15th October – Guilt with Carter Taylor Seaton (US – Barboursville, WV)

17th October – Mission to Madagascar with David Mould (US – Charleston, WV)

18th October – Mission to Madagascar with David Mould (US – Barboursville, WV)

21st October – West Virginia Book Festival

28th October – Guilt with Carter Taylor Seaton (US – South Charleston, WV)