Your basket is currently empty!

James Hastie diary discovered in New Zealand

by David Mould

In November 2023, John Parker and his wife Paulette, who own a cattle ranch in New Zealand’s North Island, were sorting through the possessions of John’s father, Tony, who had recently passed away. Among them was a precious historical resource—an 1817 diary by James Hastie.

My 2023 Blackwater Press book, Mission to Madagascar: The Sergeant, the King, and the Slave Trade, describes how Hastie, a 30-year-old East India Company sergeant with no diplomatic training, brokered a treaty with Radama, the most powerful clan chief in Madagascar, to end the export of slaves to the plantations of Mauritius, the British island colony seized from the French during the Napoleonic Wars.

Hastie became the British envoy to Madagascar and Radama’s trusted advisor, arranging for the supply of British munitions and joining Radama on campaigns to subdue rival clans. He brought in artisans to teach trades, negotiated for the London Missionary Society to open schools, and supported Radama in his power struggle against traditionalist factions. Sir Mervyn Brown, a former UK ambassador and historian of Madagascar, described Hastie as “one of the most important and attractive figures in the history of Anglo-Malagasy relations.”

For more than a century, Hastie’s diaries, written between 1817 and 1826, have been regarded by historians as the most comprehensive and insightful early nineteenth-century traveler’s account of the island’s clans, economy and culture.

The Parkers know they had found a valuable resource and learned that I had written Hastie’s biography. On November 29, John emailed me. He explained that the diary had been passed down to a Hastie descendant, his grandfather, P.H. Parker, who had emigrated from Britain to New Zealand after World War One. He had also brought with him an oil painting of Hastie and a child’s white smock top and redcoat’s uniform some children’s clothes, reportedly worn by Hastie’s son. John’s cousin had earlier donated the clothing to a museum in Madagascar’s capital, Antananarivo.

“Our issue [concerning the diary],” John wrote, “is what we should do with it and having seen you have recently written a book on the subject—you may be a good place to start.”

Within 24 hours, I was on a Zoom call with John, Paulette and John’s sister Diana. They showed me the diary, which covers the period from September 23 to October 22, 1817, when Hastie was navigating the politics of the Ovah court and building the personal relationship with Radama that led to the signing of the treaty banning the slave trade. The only known copy of Hastie’s diary for this crucial month went missing from the UK National Archives several years ago, leaving historians (me included) to rely on a 1903 French translation by the Academie Malgache.

I was, to put it mildly, thrilled. I advised the Parkers to deposit it at the King’s College London (KCL) Library, where the Foyle Special Collections already include an 1820 Hastie diary and the July 1817 diary of Thomas Locke Lewis, a naval lieutenant who arrived in Madagascar on the same ship as Hastie and conducted a reconnaissance mission before Hastie set out for the Ovah court in the central highlands. I had used both sources in my research, had a good working relationship with the Foyle archivist, Adam Ray, and had done the UK book launch at the library in June 2023.

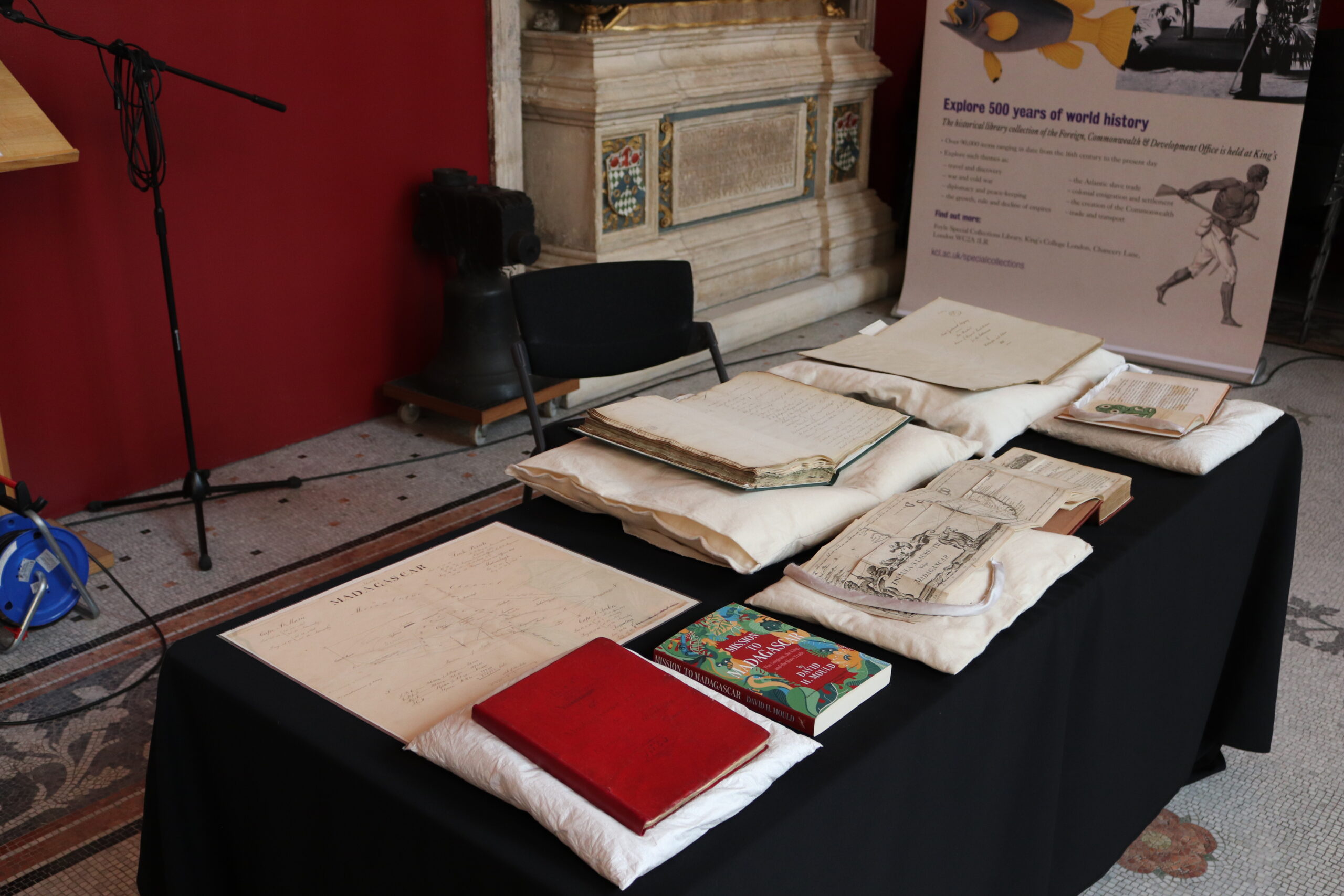

The Parkers contacted the KCL Library and agreed to donate the diary, but said they wanted to do so in person. They did so in May 2024 at a special event held in the library’s historic Weston Room which included a display of the 1820 Hastie and 1817 Lewis diaries and other Madagascar artefacts from the Foyle Collections. KCL plans to digitize the 1817 diary so it will be available to all researchers.

Comments

One response to “James Hastie diary discovered in New Zealand”

What an amazing find! It must be so satisfying to find historical documents that corroborate the amazing story that you have shared with us.

All the best,

Boni

Leave a Reply