Your basket is currently empty!

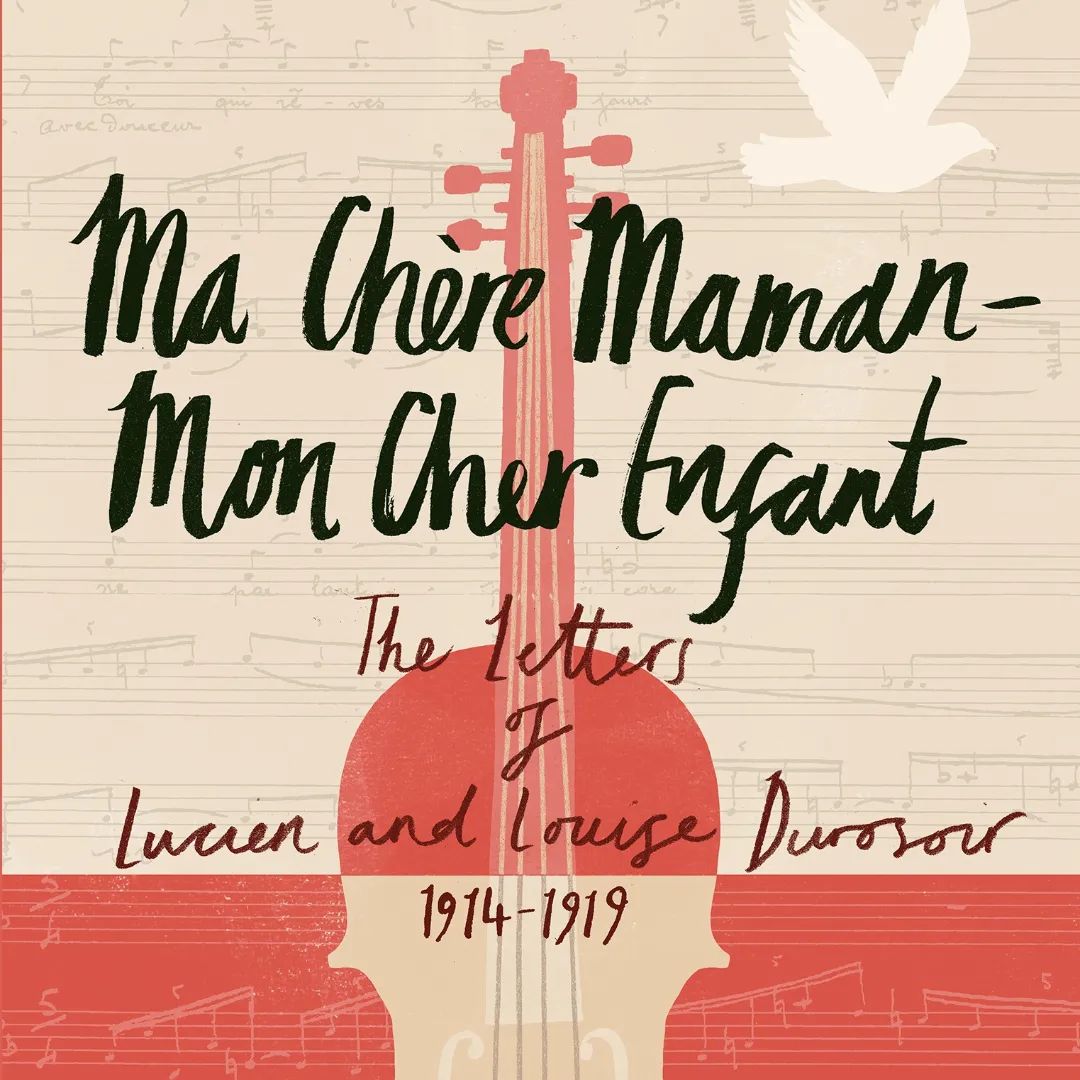

Ma Chère Maman—Mon Cher Enfant

What does French baroque music have to do with letters from World War I? The answer is not obvious but, in this case, one of simple coincidence. Two scholars of the French Baroque from both sides of the Atlantic become friends; finally, their spouses meet. The rest, as far as this book is concerned, is history. Luc Durosoir, the husband of the French scholar, told me about his retirement project—transcribing, editing, and publishing a collection of his father’s letters from World War One. I, the American spouse, was immediately taken by the unusual story of his father, Lucien Durosoir, a celebrated solo violinist, mobilized to fight the Germans at age 34, a sad twist of fate for a man who had lived in Germany, regularly visited Germany and Austria, spoke the language, and admired all aspects of German culture. His creation of a string quartet, working on and playing chamber music in the midst of the cataclysm of that war, was very far from the image I had of the war.

I eagerly started reading the collection of letters; long before I got to the part about the chamber music, I was pulled in by the early years of the war, by the enthusiasm and confidence of the French soldier (‘We’ll be home by the end of the year!’). Then by the stories of life in the trenches, and the way Lucien searched out whatever violin he could find and musicians to play with—in church, for the Red Cross, any reason to play was good enough for him. Translate the letters so my friends and family could read what I was reading—why not?

The baroque music connection turned out to be deeper than the original, chance encounter, although that was essential. Lucien became a composer after the war. He was trained in, and formed by, the music of baroque composers; his compositions are defined by his use of counterpoint, in a way unique to him, but clearly reminiscent of the baroque masters, most notably J.S. Bach. And then, surprise, my editor turns out to be a baroque flute player!

The French edition of selected letters was only the beginning of the adventure that led to Ma Chère Maman—Mon Cher Enfant. As the title suggests, there were more letters, not just those of Lucien to his mother but the ones she wrote to him. It turned out that I had found one of the rare collections of crossed correspondence from World War I. Turning the voluminous, hand-written letters of the mother, Louise, into usable text took days and days. Then I faced the daunting, sometimes sad, task of choosing which portions of them, and which portions of Lucien’s letters, to keep. I say sad, because the entirety, in French, is so moving I would have loved to keep all of it. But my readers and my publisher would not have been happy with a 1000 plus page book. The final step was to figure out the most logical way to present letters that crossed in the mail, where one letter didn’t lead easily to the response. There was no perfect solution; readers will likely find themselves a bit confused at times.

In the process, Luc and I came to know two remarkable people who were very close, who loved each other dearly, who suffered not just the hardships of war but the pain of separation and the unknown. In a recent interview I did with Luc, he commented that he understood himself better after meeting his grandmother. We should all be so fortunate.

World War I is old history now but current events make it all too relevant. The fate of northeastern France, in which whole villages disappeared in the mass destruction, in a war that Louise and Lucien both attribute to just one person, Kaiser Wilhelm, reminds us all too much of what has followed. These sets of letters paint, in a quiet, personal way, the horror and stupidity of war.

Leave a Reply