Your basket is currently empty!

Rebel Cork

The Easter Rising of 1916 was one of the major events of the twentieth century that changed the map of Europe. Following a week of violence centered in Dublin, the men who led the fight were arrested and shot at Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin. The British hoped this was the end of the rebellion; it was just the beginning.

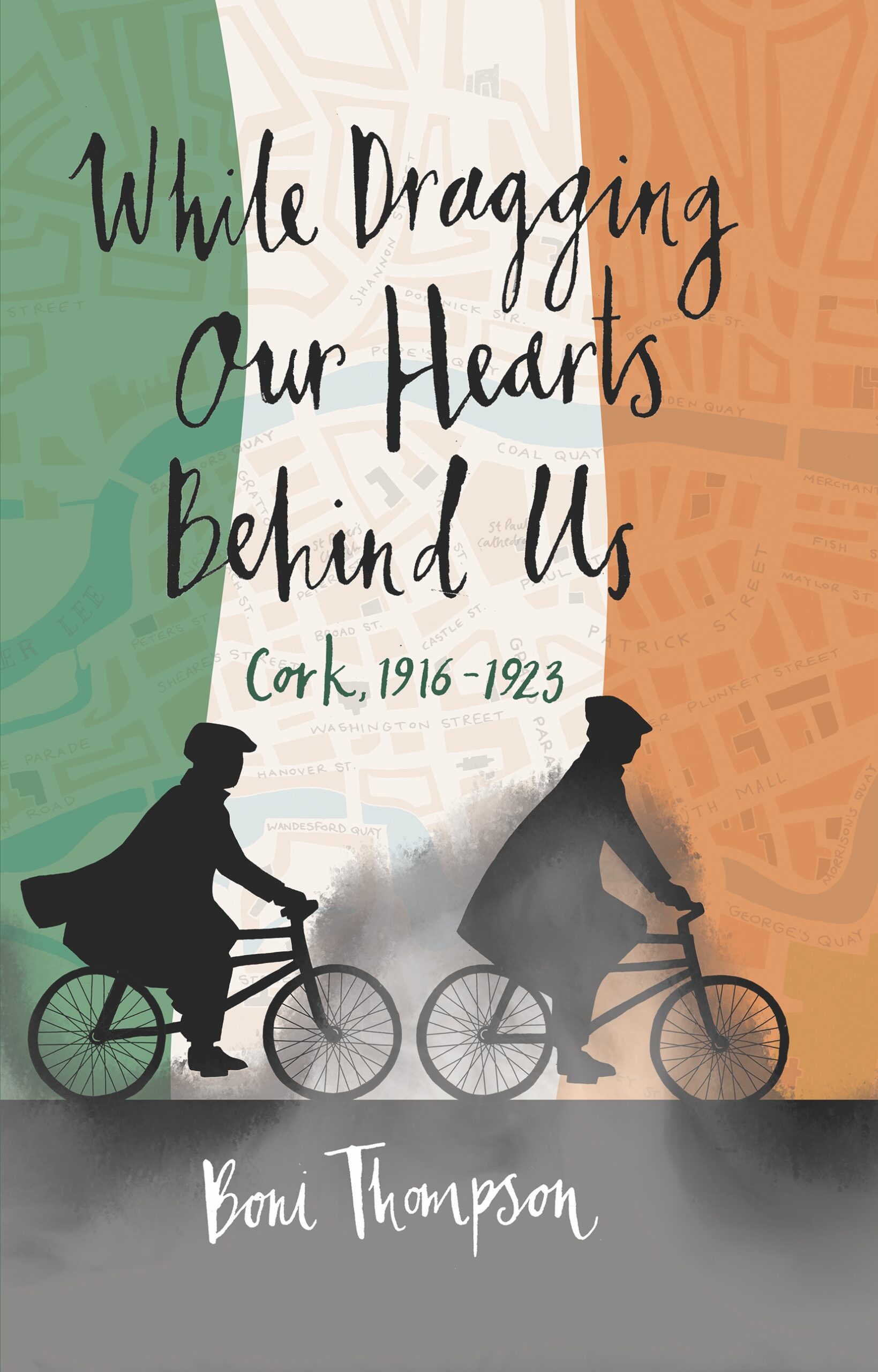

Our first book of 2024 is While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us by Boni Thompson, based on her grandfather’s time as a significant part of the 1st Cork Brigade of the IRA during the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921). Read on for how Dr. Thompson combined family history, memoir, and archival research for a gripping and harrowing account of James Fitzgerald’s work for an independent Ireland.

The story of my grandfather, James, has been a long time coming. Partly because back in the 1990s when I started to research in earnest, (not so long ago, but definitely a pre-find everything-on-the-internet world), finding any new information about the Irish War of Independence here in Canada, information that was not hagiography, or hero worship, was nigh impossible. I knew I would have to go to Ireland, to Cork, to Dublin, and various university libraries, beg for access to rare and unique documents locked up behind closed doors, and do the research myself. Afterall, nobody that I could see was talking about any of the details of that war save a few well-known escapades. It was as if a few educated men, such as Éamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith, and a few secretive intelligence men like Michael Collins made the whole thing happen by magic. I knew by the stories my grandfather had told me that this was far from the truth. Since an extended stay in Ireland was out of the question, especially with a young family in tow, I shelved the whole project before it was even started.

A few years later, on a fine autumn afternoon, I was driving home listening to CBC radio, and over the airwaves a Canadian academic from Newfoundland was introduced, by the name of Peter Hart. When the title of his book was read out, The IRA and its enemies: Violence and Community in Cork, 1916-1923, I slowed down and turned up the volume. When the interview was over, I drove straight to my local bookstore and put in my order. I was excited to hear that somebody, and a Canadian no less, was writing about the many people in Cork, James’ contemporaries, who were involved in that terrible struggle. And not only that, he was writing about the clashes between the status quo and those who would destroy it, about the violence, about the widespread nature of the conflict and he certainly didn’t sugar coat the bloody details. I fully expected James to be mentioned. He was not.

What was mentioned, however, were versions of stories, versions I didn’t recognize, men’s actions described, violence categorized and tabled, but their stories missing. These men had their actions documented, but they were somehow detached from the context in which they lived their daily lives, overseen by occupiers from another country and of another race. They were described as engaging in sectarianism, concerned with religion or class of those they fought. These versions of men, young and old, did not mesh with my own version of my grandfather nor any of the friends, fellow IRA members, or the commanding officers that he had spoken of to me, with sadness, with respect, sometimes with humour and a chuckle. The short, and it is true, sanitized tales that he shared with me when I visited him always clearly communicated one specific thing: They were fighting to get back their country, in their own hands, a fight carried on from distant generations.

They faced before them a dangerous, treacherous enemy; an enemy manned with guns and weapons that were outlawed to Irishmen, men who represented a foreign king, who manned his gaols and his dungeons and his workhouses, and who would not go quietly from that island, nor would they willingly leave behind them over 700 years of administration, of fine homes and castles, of cheap labor and lucrative business and agriculture, all while many Irish suffered poverty, lack of education, lack of rights to their own language and culture, lack of opportunity for themselves and their children. This was the enemy they faced and it would take nothing less than courage, imagination, determination, resilience and yes, sometimes cruelty, in order to be successful and drive the enemy off their island, back where they came from.

In the end of course, they did it, and a high price they paid, those men who, like James, perpetrated acts of violence in the name of freedom. Some got tangled up in violence and were changed irrevocably because of it. Others were able to walk away, reconstitute themselves as law abiding citizens. I do believe however, the vast majority of them suffered, some their whole lives long. They suffered because their worldview did not include acts of intentional violence; acts that were clearly crossing lines, lines that had been drawn for them from time immemorial. However, it seems to me, they did what they felt they had to do, no more, no less, and even as the fight got worse, more terrible than they could have imagined, they kept on.

The Irish have them to thank, now, 100 years later, a prosperous nation, free of occupation, of greedy overlords, and foreign masters. I believe it is this fact, the fact that their actions contributed to winning freedom for the nation, that allowed them to return to a normal life, despite being haunted by their youths. A life where their children had opportunities they could never have dreamed of in their own youths, because of that freedom, so hard won.

It was not easy to write my grandfather’s story. He was most definitely an insider in the centre of Cork, very close to the command structure of the IRA. The men he worked with and for understood what it meant to be an Irish Rebel fighting for their country, and the depth of resolve it took to stay with the fight, despite hardship, danger, and threats to family. This common connection with a secret knowledge of each other and what each was capable of bound them tightly together in their common task, so tightly some would suffer under torture and death before divulging information of each other. It was hard to read of kidnappings and executions, harder still to write of him participating in them. But his words stayed with me at such times, that he was a soldier of Ireland, fighting a foreign enemy, and given the history of Ireland, an often cruel and heartless one. He saw his compatriots as like-minded, trustworthy, mostly good men, strong men, doing what they believed had to be done, despite the offensive nature of some of their tasks.

The violence perpetrated by the IRA, much of it reactionary, is only a small part of the story. The way they are portrayed in academic work, gave me the impetus to tell my grandfather’s story differently, in contrast. That is, I had to tell the larger story, the context of his life and times, from his point of view, in order to see how he saw and feel how he felt in order to act in the ways he and his compatriots did. I tried to write of those historic years, 1916-1923 in Cork in such a way that his world is made apparent to us. I wanted to be true to the facts as they stand, but also, light had to be shed on the inner lives of James and his colleagues in order to have a chance at revealing the world in which those young men and women lived, their own bubble of time and place.

I did not know how I could do this without much more information. A librarian at the National Library of Ireland suggested posting an advertisement in the Cork paper. It seemed like a crazy idea to me… after all, this was the late 1990s and James had left us 10 ten years earlier at the age of 92. But in only a few short weeks, I found in my mailbox a lovely letter from a man whose mother had grown up a few doors down from James. She remembered the family well, but not James. She did mention that the younger brother had blown off his fingertips making bombs. Such a fabulous detail to build a story on! I was delighted and grateful. I wrote letters to distant relatives who had been children when James was in his 20s and 30s. They told me the hard truth. He was a difficult man in those years. I brooded on this information.

It was not until I found the newly launched compendium of witness statements posted by the Irish government after 2000 that suddenly telling his story seemed possible. I was disappointed to discover that he himself did not leave a statement, or if he did it was not included. There were however descriptions of actions taken where he was present, mentions of his attachment to headquarters, the intelligence squad, the active service unit, even the day he was shot in the head and taken to Victoria Barracks. This was exactly what I needed, but still not enough to write a full story, a story that was truly authentic and thorough.

I called up a professor at University College Cork history department. A kind and generous man, he knew of James and advised me to apply for his pension application. That took what seemed like forever, two years and two phone calls to the Irish civil department responsible. On the phone the woman in charge apologized for the delay. She said that some applications may never be made public because of the sensitive nature of the disclosures made therein. She suggested that James’s application was such a one. Shortly thereafter it arrived, a fat package of photocopied documents, letters from his old friends, some, at the time men in high places, recommending him for an officer’s pension, scolding the bureaucracy for taking so long in their deliberations. But the document that made his story possible was the list of actions that he undertook, written in his own hand, all verified by witnesses. It is a long list.

By this time, of course, the age of the internet was up and running, and so with this document I sat down and created a timeline of events, where he fit in, who he worked with, what was in the newspapers that day or evening, even the weather conditions, and tried through each event to see inside his world, indeed inside his head. From a carefree 17-year-old at the time of the Easter Rising through to the tough, hardened young man of 25 years old, who after watching beloved leaders and good friends alike suffer and die, kept the faith through it all.

I will say that this is something I still do not truly grasp, despite almost three years researching and writing about James, my grandfather. The rebel spirit in defence of a nation, of an ideal of freedom, a spirit that will not die, will not succumb, will not be cowed or broken or bought. Winston Churchill famously once said, “We have always found the Irish quite odd. They refuse to be English.” And later when speaking of the Irish Free State Act, asked the rhetorical question, “How much have we suffered in all these generations from this continued hostility?” Such statements could only be pronounced by victors, wishing to hide their culpability and reframe their guilt. We forgive Churchill, having led the world in the fight against the great evil that was Nazism, never giving up or giving in, hanging on with dogged tenacity despite setback after setback and a fierce, terrifying, enemy. Perhaps Churchill had learned something more from the Irish then what he proclaimed. Perhaps we have more to thank Irish rebels for than we realize.

While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us is already available as e-book on our web site, and pre-orders for print copies are open; publication date is March 17. We also offer an e-book + paperback bundle at a special price! To secure yours, just select ‘bundle’ in the drop-down ‘edition’ menu on our website.

And here’s some musical accompaniment that should make you want to sign up for the IRA.

Leave a Reply