Your basket is currently empty!

While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us: The Photographs

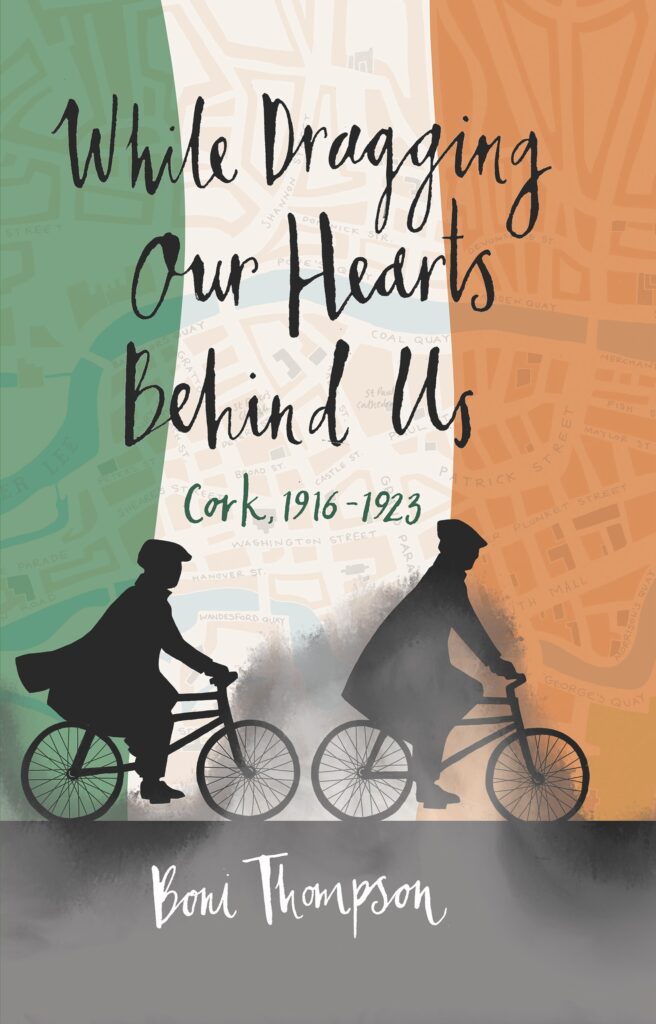

by Boni Thompson, author of While Dragging Our Hearts Behind Us.

St. Patrick’s Day is a fitting day to reflect on the publication of my grandfather’s story, 101 years after the end of the Irish Civil War, and therefore 101 years since my grandfather James left Ireland behind him. Evading the inevitable round-up of irregulars, those who were on the losing side of the war, he made his way from Liverpool to St. John, New Brunswick, Canada, and once he had worked his way by train to Toronto, sought out the assistance of Clan na Gael, a somewhat secret society of Irish Americans who passed him through customs at Niagara Falls, and took him to New York City. There he found Peter MacSwiney, brother to his good friend Sean, and the late mayor of Cork, Terrence. Peter took him in, helped him land a job quickly, and opened his eyes to everything that a world metropolis could offer, so different from a small remote city in the south of Ireland.

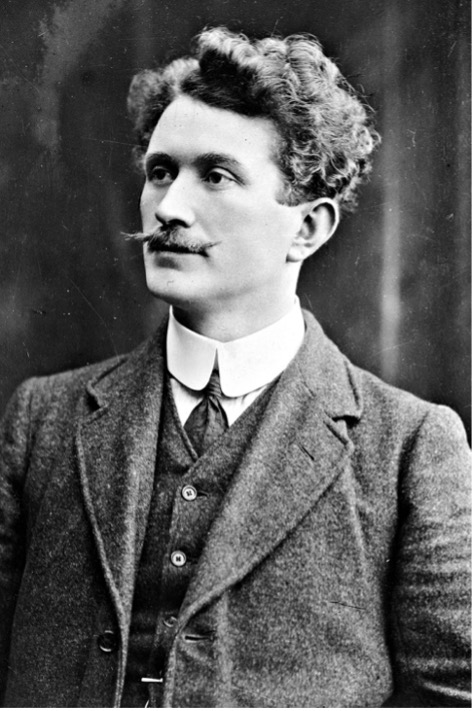

I have very few pictures of my grandfather James, Intelligence Officer, Active Service Unit member and Flying Column member of the Cork No. 1 Brigade during the Irish War of Independence. After scouring the internet many times for photographs of IRA members from 1916 and onward, I soon realized he is nowhere to be found. I am quite sure this is completely intentional on his part. The thought comes to mind that it may have been a covert policy of sorts with the early IRA to avoid being photographed. Afterall, part of how they won that war was being able to walk down the street with complete anonymity. Then again, maybe it was just good common sense. We know that leaders such as Michael Collins in Dublin and Sean O’Hegarty in Cork expected no less. I do believe it was an unspoken expectation that identities of perpetrators of various types of acts, whether violent or not, remained nameless and unrecorded. And, when looking through witness accounts, though many names are divulged for certain actions, many more are very difficult to find, despite the leadership capacities that such names implied.

This of course leads to the realization that keeping their faces and identity off the British radar was a matter of life and death for men such as James. Indeed, looking for photographs of other Intelligence unit members was also a pointless endeavour. Even the last name of his friend Mick, who travelled with him to New York City, remains a mystery to me. He may have been the Intelligence Officer Mick Leahy, or he may not have been.

Later, when they had been in America for some time, James and his Irish friends must have loosened up somewhat. Perhaps they did not think they would ever return. Or perhaps they thought that American pictures would stay in America. I have a grand total of two photos of James and his Irish compatriots taken in the mid to late twenties. They say a lot about his life there.

Pictures are a window through time. They are by definition reflections of the past, and as such they can be revelatory far beyond the subject’s awareness. The old adage ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’ may be true, looking at the subject(s), noticing the telling signs of emotion, the body language of stance and expression, the eyes, laughing, crying, suffering, joyous… such a tiny body part that can tell the reader so much. The background often gives us time frames, the model of car, the style of house, the fashion of bystanders, the skyline of cities. All of this leaks information about the subject, answering questions of who, what, where, when, sometimes how, but rarely, something which can be the most tantalizingly human question of all, why.

This picture was a surprising find. A completely serendipitous accident. The clip lasted only about 5 seconds within a larger 1-minute montage of shots of the funeral. This event occurred four years after the Easter Rising but just a few short months before O’Hegarty’s rise to Commander. James’ face is young. He is 21 years old in this shot. The tell-tale identifiers of his face, the straight mouth, the high pops of cheek bone protruding, his left ear lobe straight as an arrow, points out from his face without a curve. These were what I looked for to authenticate him in the film clip because he looks so innocent here, perhaps yet idealistic and unaware of just how terrible the fight would become. Indeed, it had barely started.

Contrast the above face with the picture below:

The effects of hunger strike, especially hunger strike resulting in death by starvation are difficult to imagine. The resolve of the men and women who undertook this extreme act of political defiance is for me, almost impossible to picture. Yet many men and women did undertake this. The fact that the outrage of the British public pressured their government to release such prisoners tells us that the effect on on-lookers, was also devestating. The death of Thomas Ashe by forcefeeding, after he undertook to hunger strike, left a horrific scar on people everywhere. 60 years after the fact, James was almost despondent describing the tragic event to me, even though Thomas Ashe was someone he never actually met in person, though a well admired and respected leader through the Easter Rising and afterwards.

Today, the laneway through which much of the IRA leadership walked up and down throughout the War of Independence looks much different than in the photo above. There is no indicator or historic plaque to mark the tremendous contribution that the Wallace sisters made to the fight in Cork City, caring for members of the Brigade, passing messages, working with Cumann na Ban, the women’s organization, and tending to top secret directives from the 3 Officers Commanding, each in his turn, not to mention the daily risks undertaken as a secret meeting place, day and night. Is it because they are women? Maybe. But remember also that O’Hegarty, the fierce commander who took over after the first two republican mayors, MacCurtain and MacSwiney, also seems to be forgotten to Cork history.

This was a devastating blow to many religious men in the Cork No 1 Brigade. Father Dominic was a tremendous supporter of the Irish Republican Army. He had seen action in Gallipoli as a chaplain during the Great War. Clearly after such an experience he had a thorough understanding of the terrible effects of war on body and soul. He also understood the political determination to fight for freedom from oppression and considered actions against the oppressor as morally correct. This was diametrically opposed to the Bishop of Cork’s stance, which was to excommunicate all Catholic IRA members in Cork if participating in actions against the status quo.

Note the inside and outside walls that the prisoners had to scale on a dark moonless night after breaking through an old hidden door at the back of the cell block. With a makeshift ladder hidden under the grass, they were able to escape the confines of the prison and find a row boat to get to Cobh.

I believe that photographs play an important part in our understanding of history. They sometimes bring into sharp focus, people, places and actions that may seem distant and uncertain, despite testimony, story, or history books. But photographs, though they help to clarify many details of events in the past, cannot help us see into the minds of those who came before us. Why does James participate in the IRA at all? Many of his contemporaries did not. Why does he feel such resolve to stick with the fight, even in the face of much hardship, participation in events that had his 20-year-old auburn hair turn white in short order, and the general situation of disorder, fear, and grave danger of capture, arrest, and/or execution any time he walked the streets of Cork? I do not know the answer to these questions.

Were I given the opportunity to talk to my grandfather again, now, as an educated adult, and not a star-struck teenager, I would ask him much different questions. Questions such as, how bad was the world in which you lived, that you should undertake this fight, a fight that to outside eyes seemed ridiculous, foolish, impossible to win? How cruel was the world you were born into, how hopeless that such a fight, a wild gamble at first glance, seemed to you the right thing to do? I have seen photographs from that era of children in bare feet and rags in Cork City, pictures of Dublin slums, the worst in the western world at the turn of the century. I have read of poverty so pervasive and insidious, people in remote rural areas surviving without proper outdoor clothing, of Irishmen prosecuted for fishing in rivers owned by British aristocrats who visited once or twice a year. I would ask him, as to the men he followed, and obeyed, acted on behalf of, how visionary were such men that they gave you the seeds of hope of a different kind of world? Seeds of hope in a world run by Irishmen, British castles and prisons no longer, education and jobs and prosperity a given. I would ask him, was it worth it? the wretched things expected of you? the constant danger? the loss of such beloved visionary leaders to violence? the loss of good friends in similar ways? I would ask him these questions, but, I know what his answer would be. It would be a simple “Yes,” and perhaps a short comment such as… “Sure hadn’t the Irish been fighting for freedom for 700 years? It was my generation that made it happen. It was worth it.”

Leave a Reply